Visayans

Kabisay-an / Mga Bisaya | |

|---|---|

A Visayan couple of noble blood, Boxer Codex, ca. 1590 | |

| Total population | |

| 33,463,654[citation needed] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

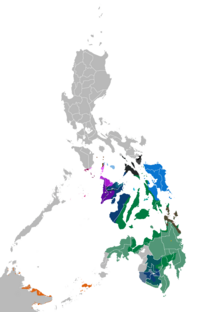

| Visayas, large parts of Mindanao, southernmost parts of Luzon, the rest of the Philippines and overseas communities | |

| Languages | |

| Native Bisayan languages Also Filipino • English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity: Roman Catholic, Aglipayan, Evangelicals, remaining belongs to United Church of Christ in the Philippines, Iglesia ni Cristo; Sunni Islam; Hinduism; Animism and other religions[1] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tausūg people, Zamboangueño people, Tagalog people, Austronesian people and other Filipinos |

Visayans (Visayan: mga Bisaya; local pronunciation: [bisaˈjaʔ]) or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic family group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao. They are composed of numerous distinct ethnic groups, many unrelated to each other. When taken as a single group, they number around 33.5 million. The Visayans, like the Luzon Lowlanders (Tagalogs, Bicolanos, Ilocanos, etc.) were originally predominantly animist-polytheists and broadly share a maritime culture until the 16th century when the Spanish empire enforced Catholicism as the state religion. In more inland or otherwise secluded areas, ancient animistic-polytheistic beliefs and traditions either were reinterpreted within a Roman Catholic framework or syncretized with the new religion. Visayans are generally speakers of one or more of the distinct Bisayan languages, the most widely spoken being Cebuano, followed by Hiligaynon (Ilonggo) and Waray-Waray.[2]

Terminology

[edit]"Visayan" is the anglicization of the hispanized term Bisayas (archaic Biçayas), in turn derived from Visayan Bisaya. Kabisay-an refers both to the Visayan people collectively and the islands they have inhabited since prehistory, the Visayas. The exact meaning and origin of the name Bisaya is unknown. The first documented use of the name is possibly by Song-era Chinese maritime official Zhao Rugua who wrote about the "Pi-sho-ye", who raided the coasts of Fujian and Penghu during the late 12th century using iron javelins attached to ropes as their weapons.[3][4][5]

Visayans were first referred to by the general term Pintados ("the painted ones") by the Spanish, in reference to the prominent practice of full-body tattooing (batok).[6] The word Bisaya, on the other hand, was first documented in Spanish sources as evidenced by at least one instance of a place named "Bisaya" in coastal eastern Mindanao as reported by the Loaisa (c.1526), Saavedra (c.1528), and the Villalobos (c.1543) expeditions.

At the advent of Spanish colonialism after the Legazpi Expedition in 1565, the term Visayan was first applied only to the people of Panay and to their settlements eastward in the island of Negros, and northward in the smaller islands, which now compose the province of Romblon. In fact, even at the early part of Spanish colonialization of the Philippines, the Spaniards used the term Visayan only for these areas. While the people of Cebu and nearby areas were for a long time known only as Pintados.[7] The name Visayan was later extended to them because, as several of the early writers state (especially in the writings of the Jesuit Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro published in 1801),[8] albeit erroneously, their languages are closely allied to the Visayan "dialect" of Panay.[9]

Gabriel Rivera, a captain of the Spanish royal infantry in the Philippine Islands, also distinguished Panay from the rest of the Pintados Islands. In his report (dated 20 March 1579) regarding a campaign to pacify the natives living along the rivers of Mindanao (a mission he received from Dr. Francisco de Sande, Governor and Captain-General of the Archipelago), Ribera mentioned that his aim was to make the inhabitants of that island "vassals of King Don Felipe... as are all the natives of the island of Panay, the Pintados Islands, and those of the island of Luzon..."[10]

In Book I, Chapter VII of the Labor Evangelica (published in Madrid in 1663), Francisco Colin, S.J. described the people of Iloilo as Indians who are Visayans in the strict sense of the word (Indios en rigor Bisayas), observing also that they have two different languages: Harayas and Harigueynes,[11] which are actually the Karay-a and Hiligaynon languages.

However, in Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas (1609) by Antonio de Morga, he specifies that the name "Biçaya" is synonymous with Pintados.[12]

"South of this district lie the islands of Biçayas, or, as they are also called, Pintados. They are many in number, thickly populated with natives. Those of most renown are Leite, Ybabao, Çamar, Bohol, island of Negros, Sebu, Panay, Cuyo, and the Calamianes. All the natives of these islands, both men and women, are well-featured, of a good disposition, and of better nature, and more noble in their actions than the inhabitants of the islands of Luzon and its vicinity.

They differ from them in their hair, which the men wear cut in a cue, like the ancient style in España. Their bodies are tattooed with many designs, but the face is not touched. They wear large earrings of gold and ivory in their ears, and bracelets of the same; certain scarfs wrapped round the head, very showy, which resemble turbans, and knotted very gracefully and edged with gold. They wear also a loose collarless jacket with tight sleeves, whose skirts reach half way down the leg. These garments are fastened in front and are made of medriñaque and colored silks. They wear no shirts or drawers, but bahaques of many wrappings, which cover their privy parts, when they remove their skirts and jackets. The women are good-looking and graceful. They are very neat, and walk slowly. Their hair is black, long, and drawn into a knot on the head. Their robes are wrapped about the waist and fall downward. These are made of all colors, and they wear collarless jackets of the same material. Both men and women go naked and without any coverings, and barefoot, and with many gold chains, earrings, and wrought bracelets.

Their weapons consist of large knives curved like cutlasses, spears, and caraças. They employ the same kinds of boats as the inhabitants of Luzon. They have the same occupations, products, and means of gain as the inhabitants of all the other islands. These Visayans are a race less inclined to agriculture, and are skilful in navigation, and eager for war and raids for pillage and booty, which they call mangubas. This means "to go out for plunder."

. . .

The language of all the Pintados and Biçayas is one and the same, by which they understand one another when talking, or when writing with the letters and characters of their own which they possess. These resemble those of the Arabs. The common manner of writing among the natives is on leaves of trees, and on bamboo bark.

— Antonio de Morga, Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas (1609) translated in Morga's Philippine Islands (1907) by Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, [12]

The first Spanish-Visayan dictionary written was for the Waray language in the Bocabulario de la lengua Bisaya by Mateo Sánchez, which was completed in 1617 in Leyte. This was followed by the Bocabulario de la lengua Bisaya-Hiligueyna y Haraía de las islas de Panay y Sugbu, y para las demás islas (1637) by Alonso de Méntrida which in turn was for the Hiligaynon language, with notes on the Aklanon and Kinaray-a languages. Both these works demonstrate that the term Bisaya was used as a general term for Visayans by the Spanish.[13]

Another general term for Visayans in early Spanish records is Hiligueinos (also spelled Yliguenes, Yligueynes, or Hiligueynos; from Visayan Iligan or Iliganon, meaning "people of the coast"). It was used by the Spanish conquistador Miguel de Loarca in Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (1582) as a general name for coastal-dwelling Visayans not only in Panay, but also Cebu, Bohol, and Western Negros. Today, the demonym is only used specifically for the Hiligaynon people, a major Visayan subgroup.[14]

In Northern Mindanao, Visayans (both Mindanao natives and modern migrants) are also referred to by the Lumad as the dumagat ("sea people", from the root word dagat - "sea"; not to be confused with the Dumagat Aeta in Luzon). This was to distinguish the coast-dwelling Visayans from the Lumad of the interior highlands and marshlands.[15]

Regions with significant populations

[edit]The following regions and provinces in the Philippines have a sizeable or predominant Visayan population:

| Mimaropa and Bicol | Western Visayas | Negros | Central Visayas | Eastern Visayas | Zamboanga Peninsula | Northern Mindanao | Caraga Region | Davao Region | Soccsksargen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

History

[edit]Classical period

[edit]

The Visayans first encountered Western Civilization when Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan reached the island of Homonhon, Eastern Samar in 1521.[17] The Visayas became part of the Spanish colony of the Philippines and the history of the Visayans became intertwined with the history of the Philippines. With the three centuries of contact with the Spanish Empire via Mexico and the United States, the islands today share a culture[18] tied to the sea[19] later developed from an admixture of indigenous lowland Visayans, Han Chinese, Indian, and American influences.

Spanish colonial period

[edit]The first Filipino people encountered by the Magellan expedition (c. 1521) were Visayans from the island of Suluan; followed by two rulers of the Surigaonon and Butuanon people on a hunting expedition in Limasawa, Rajah Colambu and Rahah Siaui; and finally Rajah Humabon of Cebu. Magellan describes the Suluanon people he encountered as "painted" (tattooed), with gold earrings and armlets, and kerchiefs around their heads. They described Rajah Colambu as having dark hair that hung down to his shoulders, tawny skin, and tattoos all throughout his body. They also noted the large amount of gold ornaments he wore, from large gold earrings to gold tooth fillings. Rajah Colambu wore embroidered patadyong that covered him from the waist to the knees, as well as a kerchief around his head. They also described the boloto (bangka) and the large balanghai (balangay) warships, and the custom of drinking palm wine (uraka) and chewing areca nut. They also described the queen of Cebu as being young and beautiful and covered in white and black cloth. She painted her lips and nails red, and wore a large disc-shaped hat (sadok) made from elaborately-woven leaves.[20]: 132–161

The 16th century marks the beginning of the Christianization of the Visayan people, with the baptism of Rajah Humabon and about 800 native Cebuanos. The Christianization of the Visayans and Filipinos in general, is commemorated by the Ati-Atihan Festival of Aklan, the Dinagyang Festival of Iloilo, and the Sinulog festival the feast of the Santo Niño de Cebu (Holy Child of Cebu), the brown-skinned depiction of the Child Jesus given by Magellan to Rajah Humabon's wife, Hara Amihan (baptized as Queen Juana). By the 17th century, Visayans already took part in religious missions. In 1672, Pedro Calungsod, a teenage indigenous Visayan catechist and Diego Luis de San Vitores, a Spanish friar, were both martyred in Guam during their mission to preach Christianity to the Chamorro people.[21]

By the end of the 19th century, the Spanish Empire weakened after a series of wars with its American territories. The surge of newer ideas from the outside world thanks to the liberalization of trade by the Bourbon Spain fostered a relatively larger middle class population called the Ilustrados or "the Enlightened Ones." This then became an incentive for the new generation of educated political visionaries to fulfill their dreams of independence from three centuries of colonial rule. Some prominent leaders of the Philippine Revolution in the late 19th century were Visayans. Among leaders of the Propaganda movement was Graciano López Jaena, the Ilonggo who established the propagandist publication La Solidaridad (The Solidarity). In the Visayan theater of the Revolution, Pantaleón Villegas (better known as León Kilat) led the Cebuano revolution in the Battle of Tres de Abril (April 3). One of his successors, Arcadio Maxilom, is a prominent general in the liberalization of Cebu.[22] Earlier in 1897, Aklan fought against the Spaniards with Francisco Castillo and Candido Iban at the helm. Both were executed after a failed offensive.[23] Martin Delgado led the rebellion in neighboring Iloilo. Led by Juan Araneta with the assistance of Aniceto Lacson, Negros Occidental was freed while Negros Oriental was liberated by Diego de la Viña. The former would be called the Negros Revolution or the Cinco de Noviembre.[24] Movements in Capiz were led by Esteban Contreras with the aid of Alejandro Balgos, Santiago Bellosillo and other Ilustrados.[25][26] Meanwhile, Leandro Locsin Fullon spearheaded the liberalization of Antique.[27] Most of these revolutionaries would continue their fight for independence until the Philippine–American War. There was also a less heard and short-lived uprising called the Igbaong Revolt which occurred in Igbaong, Antique steered by Maximo and Gregorio Palmero. This revolt, however, was secularly-motivated as they clamored for a more syncretic form of religion based on Visayan animist traditions and Christianity.[28]

Federal State of the Visayas

[edit]

At the peak of the Philippine Revolution, anti-colonial insurgencies sprung from Luzon up to the Visayas. Despite military support from the Tagalog Republic led by Emilio Aguinaldo, Visayan revolutionary leaders were skeptical toward the real motives of the Tagalogs.[29] Such ethnic animosity was notable to the point that local Visayan leaders demanded forces sent from the north to surrender their armaments and were prohibited to leave revolutionary bases. Moreover, this apprehension led to the full declaration of the Federal State of Visayas on December 12, 1898.[30] This short-lived federal government, based in Iloilo, was an accumulation of revolutionary movements across Panay and Negros. The following were the elected officials four days prior to the declaration:[31]

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| General-President | Anecito Lacson |

| Treasurer | Eusebio Luzurriaga |

| Executive Secretary | Melecio Severino |

| Secretary of War | Juan Araneta |

| Secretary Of Interior | Simeón Lizares |

| Secretary of Public Works | Nicolás Gólez |

| Secretary of Justice | Antonio Jayme Ledesma |

| Secretary of Agriculture and Commerce | Agustín Amenablar |

The federation was immediately formed upon the merger of the Cantonal Government of Negros,[32] the Cantonal Government of Bohol and the Provisional Government of the District of Visayas (based in Panay) which included Romblon. It was said to be based on American federalism and Swiss confederacy. Despite their skepticism towards Malolos, the Visayan government proclaimed its loyalty to the Luzon-based republic while maintaining their own governance, tax collection and army. Apolinario Mabini, then the prime minister of the Malolos republic convinced the Visayan leaders that the Malolos Constitution was only provisional and that the governments in Visayas and Mindanao were promised the power to co-ratify it.[33][34]

American colonization

[edit]

After the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the American colonial government saw the integral part of indigenous elites particularly in Negros in local affairs. This was a different move compared to the previous Spanish imperialists who created a racial distinction between mestizos and native Austronesians (indios). As such, this paved the way for a homogenous concept of a Filipino albeit initially based on financial and political power. These said elites were the hacienderos or the landed, bourgeois-capitalist class concentrated within the sugar cane industry of Negros. The Americans' belief that these hacienderos would be strategic elements in their political hold within the newly acquired colony bolstered the drafting of a separate colonial constitution by and for the sugar industry elites. This constitution likewise established the Negros Cantonal Government. This ensured that the island of Negros would be governed by an indigenous civilian government in contrast to the rest of colonist-controlled areas governed by the American-dominated Philippine Commission.[35]

During this period, the eastern islands of Samar, Leyte and Biliran (including Marinduque) were directly governed by the Malolos Republic through Vicente Lukban and later by Ambrosio Mojica.[36] Meanwhile, prior to the full abolition of the federal government on November 12, 1899, Emilio Aguinaldo appointed Martin Delgado as the civil and military governor of Iloilo on April 28, 1899, upon American invasion of Antique. The federal government, much to its rejection of the Cebuano leaders who supported the Katipunan cause, was dissolved upon the Iloilo leaders' voluntary union with the newly formed First Philippine Republic.[37] Other factors which led to Aguinaldo forcing the Visayans to dissolve their government was due to the federation's resistance from reorganizing its army and forwarding taxes to Malolos.[38]

Contemporary

[edit]Since Philippine independence from the United States, there have been four Philippine Presidents from the Visayan regions: the Cebuano Sergio Osmeña, the Capiznon Manuel Roxas, the Boholano Carlos P. García (who is actually of Ilocano descent through his parents from Bangued, Abra), and the Davaoeño Rodrigo Duterte.

In addition, the Visayas has produced three Vice-Presidents, four Senate Presidents, nine Speakers of the House, six Chief Justices, and six Presidential Spouses including Imelda Marcos, a Waray. The then-president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo is also half Cebuano. Former president Rodrigo Duterte, who is of Visayan ethnicity, also has Leyteño roots. Incumbent president Bongbong Marcos, is of Visayan descent through his Waray mother Imelda Marcos. In international diplomacy the Visayas has produced a United Nations Undersecretary general, the Negros Occidental native Rafael M. Salas who served as the Head of the UNFPA. In the lines of religion, there have been three Visayan Cardinals, namely Julio Rosales from Samar, Jaime Sin from Aklan and Jose Advincula from Capiz. The first Visayan and second Filipino that was canonized is Pedro Calungsod.[39]

Throughout centuries, non-Visayan groups, most notably migrants from Luzon and foreigners such as the Chinese, have settled in predominantly-Visayan cities in Visayas like Iloilo, Bacolod, Dumaguete and Cebu and Mindanao such as Cagayan de Oro, Iligan, Davao and General Santos.[40][41] These Filipino-Chinese have been assimilated to mainstream society. One factor would be the limited number of Chinese schools in the Visayas which help maintain the Chinese identity and a stronger sense of a distinct community.[42] Many of them, particularly the younger generation, have been de-cultured from Chinese traditions, share values about family and friends with other Filipinos, and do not write or speak Chinese well.[43][44] Mexicans, Spaniards and Frenchmen were also settlers in the Visayas and can be found in the Visayan provinces of Negros, Cebu, Leyte and Iloilo.[45]

Meanwhile, Negritos, locally called Ati, have also been assimilated into mainstream Visayan society.

In Mindanao, migrant ethnic individuals from Luzon as well as Lumad assimilated into a society of Cebuano-speaking majority (Hiligaynon-speaking majority in the case of Soccsksargen) over many years, identifying themselves as Visayans upon learning Cebuano (or Hiligaynon) despite many of them still know and retain their non-Visayan roots and some speak their ancestor's language fluently at least as their second or third languages, since Mindanao is melting pot of different cultures as a result of southward migration from Luzon and Visayas to the island since 20th century. Descendants of these migrant Luzon ethnic groups especially newer generations (as Mindanao-born natives) and Lumad individuals now speak Cebuano or Hiligaynon fluently as their main language with little or no knowledge of their ancestors' native tongues at the time of leaving their respective homelands in Luzon heading south, as for the Lumad, due to the contact with Cebuano- and Hiligaynon-speaking neighbors.[46]

Visayans have likewise migrated to other parts of the Philippines, especially Metro Manila and Mindanao. The Visayans have also followed the pattern of migration of Filipinos abroad and some have migrated to other parts of the world starting from the Spanish and American period and after World War II. Most are migrants or working as overseas contract workers.

Language

[edit]

Ethnic Visayans predominantly speak at least one of the Bisayan languages, most of which are commonly referred as Binisaya or Bisaya. The table below lists the Philippine languages classified as Bisayan languages by the Summer Institute of Linguistics. Although all of the languages indicated below are classified as "Bisayan" by linguistic terminology, not all speakers identify themselves as ethnically or culturally Visayan. The Tausūg, a Moro ethnic group, only use Bisaya to refer to the predominantly Christian lowland natives which Visayans are popularly recognized as.[47] This is a similar case to the Ati, who delineate Visayans from fellow Negritos. Conversely, the Visayans of Capul in Northern Samar speak Abaknon, a Sama–Bajaw language, as their native tongue.

| Language | Speakers | Date/source |

|---|---|---|

| Aklanon | 394,545 | 1990 census |

| Ati | 1,500 | 1980 SIL |

| Bantoanon (Asi) | 200,000 | 2002 SIL |

| Butuanon | 34,547 | 1990 census |

| Caluyanon | 30,000 | 1994 SIL |

| Capiznon | 638,653 | 2000 |

| Cebuano1 | 20,043,502 | 1995 census |

| Cuyonon | 123,384 | 1990 census |

| Hiligaynon1 | 7,000,000 | 1995 |

| Inonhan | 85,829 | 2000 WCD |

| Kinaray-a | 377,529 | 1994 SIL |

| Malaynon | 8,500 | 1973 SIL |

| Masbatenyo | 350,000 | 2002 SIL |

| Porohanon | 23,000 | 1960 census |

| Ratagnon | 310 | 2010 Ethnologue |

| Romblomanon | 200,000 | 1987 SIL |

| Sorsogon, Masbate | 85,000 | 1975 census |

| Sorsogon, Waray | 185,000 | 1975 census |

| Surigaonon | 344,974 | 1990 census |

| Tausug2 | 2,175,000 | 2012 SIL |

| Waray-Waray | 2,437,688 | 1990 census |

| Total | 33,463,654 |

1 Philippines only.

2 Philippines only; 1,022,000 worldwide.

Culture

[edit]Tattoo

[edit]Like most other pre-colonial ethnic groups in the Philippines and other Austronesian groups, tattooing was widespread among Visayans. The original Spanish name for the Visayans, Los Pintados ("The Painted Ones") was a reference to the tattoos of the Visayans. Antonio Pigafetta of the Magellan expedition (c. 1521) repeatedly describes the Visayans they encountered as "painted all over".[20]

Tattooing traditions were lost over time among almost all Visayans during Christianization in the Spanish colonial period. It is unclear whether the related Tausug people, who are a subset of southern Visayans who Islamized from the 13th century, practiced tattooing before they took up Islam. Today, traditional tattooing among Visayans only survives among some of the older members of the Sulodnon people of the interior highlands of Panay, the descendants of ancient Visayans who escaped Spanish conversion.[48]

Tattoos were known as batuk (or batok) or patik among Visayans. These terms were also applied to identical designs used in woven textiles, pottery, and other decorations. Tattooed people were known generally as binatakan or batokan (also known to the Tagalog people as batikan, which also means "renowned" or "skilled"). Both sexes had tattoos. They were symbols of tribal identity and kinship, as well as bravery, beauty, and social status. It was expected of adults to have them, with the exception of the asog (feminized men) for whom it was socially acceptable to be mapuraw or puraw (unmarked). Tattoos were so highly regarded that men will often just wear a loincloth (bahag) to show them off.[13][49]

"The principal clothing of the Cebuanos and all the Visayans is the tattooing of which we have already spoken, with which a naked man appears to be dressed in a kind of handsome armor engraved with very fine work, a dress so esteemed by them they take it for their proudest attire, covering their bodies neither more nor less than a Christ crucified, so that although for solemn occasions they have the marlotas (robes) we mentioned, their dress at home and in their barrio is their tattoos and a bahag, as they call that cloth they wrap around their waist, which is the sort the ancient actors and gladiators used in Rome for decency's sake."

— Pedro Chirino, Relación de las Islas Filipinas (1604), [13]

The Visayan language itself had various terminologies relating to tattoos like kulmat ("to show off new tattoos) and hundawas ("to bare the chest and show off tattoos for bravado"). Men who were tattooed but have not participated in battles were scorned as halo (monitor lizard), in the sense of being tattooed but undeserving. Baug or binogok referred to the healing period after being tattooed. Lusak ("mud") refers to tattoos that had damaged designs due to infection. Famous heroes covered in tattoos were known as lipong.[13]

Tattoos are acquired gradually over the years, and patterns can take months to complete and heal. They were made by skilled artists using the distinctively Austronesian hafted tattooing technique. This involves using a small hammer to tap the tattooing needle (one or several) set perpendicularly on a wooden handle in an L-shape (hence "hafted"). The ink was made from soot or ashes and water or plant extracts (like those from Cayratia trifolia) and was known as biro. The tattooing process were sacred events that required chicken or pig sacrifices to the ancestor spirits (diwata). Artists were usually paid with livestock, heirloom beads, or precious metals.[13][50][48]

The first tattoos were acquired during the initiation into adulthood. They are initially made on the ankles, gradually moving up to the legs and finally the waist. These tattoos were known as hinawak ("of the waist"). These were done on all men, and did not indicate special status. Tattoos on the upper body, however, were only done after notable feats (including in love) and after participation in battles. Once the chest and throat are covered, tattoos are further applied to the back. Tattoos on the chin and face (reaching up to the eyelids) are restricted to the most elite warriors. These face tattoos are called bangut ("muzzle") or langi ("gaping [jaws/beaks]") and are often designed to resemble frightening masks. They may also be further augmented with scarification (labong) burned into the arms. Women were tattooed only on the hands in very fine and intricate designs resembling damask embroidery.[13][51]

Tattoo designs varied by region. They can be repeating geometric designs, stylized representations of animals (like snakes and lizards), and floral or sun-like patterns. The most basic design was the labid, which was an inch-wide continuous tattoo that covered the legs to the waist in straight or zigzagging lines. Shoulder tattoos were known as ablay; chest tattoos up to the throat were known as dubdub; and arm tattoos were known as daya-daya (also tagur in Panay).[13]

Other body modifications

[edit]In addition to tattoos, Visayans also had other body modifications. These include artificial cranial deformation, in which the forehead of infants was pressed against a comb-like device called tangad. The ideal skull shape for adults was for the forehead to slope backwards with a more elongated back part of the skull. Adults with skulls shaped this way were known as tinangad, in contrast with those of unshaped skulls called ondo. Men were also circumcised (more accurately supercised), practiced pearling, or wore pin-shaped genital piercings called tugbuk which was anchored by decorative rivets called sakra. Both men and women also had ear piercings (1 to 2 on each ear for men, and 3 to 4 for women) and wore huge ring-shaped earrings, earplugs around 4 cm (1.6 in) wide, or pendant earrings.[13] Gold teeth fillings were also common for renowned warriors. Teeth filing and teeth blackening were also practiced.[48][52][53][54]

Precolonial Religion

[edit]Pre-Christianity

[edit]

Prior to the arrival of Catholicism, precolonial Visayans adhered to a complex animist and Hindu-Buddhist system where spirits in nature were believed to govern all existing life. Similar to other ethnic groups in the Philippines such as the Tagalogs who believed in a pantheon of gods, the Visayans also adhered to deities led by a supreme being. Such belief, on the other hand, was misinterpreted by arriving Spaniards such as Jesuit historian Pedro Chirino to be a form of monotheism.[55] There are Kaptan and Magwayan, supreme god of the sky and goddess of the sea and death, respectively. They in turn bore two children, Lihangin, god of wind, and Lidagat, goddess of the sea. Both aforementioned gods had four children, namely Likabutan, the god of the world, Liadlaw, the god of the sun, Libulan, the god of the moon, and Lisuga, the goddess of the stars.[56] People believed that life transpires amidst the will of and reverence towards gods and spirits. These deities who dwell within nature were collectively called the diwata (a local adaptation of the Hindu or Buddhist Devata).[57] The Visayans adored (either for fear or veneration) various Diwatas . Early Spanish colonizers observed that some of these deities of the Visayas, have sinister characters, and so, the colonizers called them evil gods. These Diwatas live in rivers, forests, mountains, and the natives fear even to cut the grass in these places believed to be where the lesser gods abound.[58] These places are described, even now (after more than four hundred years of Christianization in the region), as mariit (enchanted and dangerous). The natives would make panabi-tabi (courteous and reverent request for permission) when inevitably constrained to pass or come near these sites. Miguel de Loarca in his Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) described them. Some are the following:

- Barangao, Ynaguinid, and Malandok: a trinity of deities invoked before going to war, or before plundering expeditions[59]

- Makaptan: the god who dwells in the highest sky, in the world that has no end. He is a bad god, because he sends disease and death if has not eaten anything of this world or has not drunk any pitarillas. He does not love humans, and so he kills them.[60]

- Lalahon: the goddess who dwells in Mt. Canlaon, from where she hurls fire. She is invoked for harvests. When she does not grant the people good harvest, she sends them locusts to destroy and consume the crops.[61]

- Magwayen: the god of the oceans; and the father (in some stories the mother) of water goddess Lidagat, who after her death decided to ferry souls in the afterworld.[62]

- Sidapa: another god in the sky, who measures and determines the lifespan of all the new-born by placing marks on a very tall tree on Mt. Madja-as, which correspond to each person who come into this world. The souls of the dead inhabitants go to the same Mt. Madja-as.[62]

Some Spanish colonial historians, including Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, would classify some heroes and demigods of the Panay epic Hinilawod, like Labaw Donggon, among these Diwatas.[63]

Creation of the first man and woman

[edit]In the above-mentioned report of Miguel de Loarca, the Visayans' belief regarding the origin of the world and the creation of the first man and woman was recorded. The narrative says:[64]

The people of the coast, who are called Yligueynes, believed that the heaven and earth had no beginning and that there were two gods, one called Captan and the other Maguayen. They believed that the breeze and the sea were married; and that the land breeze brought forth a reed, which was planted by the god Captan. When the reed grew, it broke into two sections, from which came a man and a woman. To the man they gave the name Silalac, and that is the reason why men from that time on have been called lalac; the woman they named Sicavay, and henceforth women have been called babaye...'

One day the man asked the woman to marry him for there were no other people in the world; but she refused, saying they were brother and sister, born of the same reed, with only one know between them. Finally, they agreed to ask the advice from the tunnies of the sea and from the doves of the earth. They also went to the earthquake, which said that it was necessary for them to marry, so that the world might be peopled.

Death

[edit]The Visayans believed that when the time comes for a person to die, the diwata Pandaki visits him to bring about death. Magwayen, the soul ferry god, carries the souls of the Yligueynes to the abode of the dead called Solad.[65] But when a bad person dies, Pandaki brings him to the place of punishment in the abode of the dead, where his soul will wait to move on to the Ologan or heaven. While the dead is undergoing punishment, his family could help him by asking the priests or priestesses to offer ceremonies and prayers so that he might go to the place of rest in heaven.[66]

Shamans

[edit]The spiritual leaders were called the Babaylan. Most of the Babaylan were women who, for some reasons, the colonizers described as "lascivious" and astute. On certain ceremonial occasions, they put on elaborate apparel, which appear bizarre to Spaniards. They would wear yellow false hair, over which some kind of diadem adorn and, in their hands, they wielded straw fans. They were assisted by young apprentices who would carry some thin cane as for a wand.[67]

Notable among the rituals performed by Babaylan was the pig sacrifice. Sometimes chicken were also offered. The sacrificial victims were placed on well adorned altars, together with other commodities and with the most exquisite local wine called Pangasi. The Babaylan would break into dance hovering around these offerings to the sound of drums and brass bells called Agongs, with palm leaves and trumpets made of cane. The ritual is called by the Visayans "Pag-aanito".[68]

Spirits were referred to as umalagad (called anito in Luzon).[69] These refer to ancestors, past leaders or heroes also transfigured within nature. Beside idols symbolizing the umalagad were food, drinks, clothing, precious valuables or even a sacrificial animal offered for protection of life or property. Such practice was a form of ancestor worship. Furthermore, these rituals surrounding the diwata and umalagad were mediated by the babaylan who were highly revered in society as spiritual leaders. These intercessors were equivalent to shamans, and were predominantly women or were required to have strong female attributes such as hermaphrodites and homosexuals. Old men were also allowed to become one.[70] One notable example is Dios Buhawi who ruled a politico-religious revolt in Negros Oriental at the beginning of the Philippine Revolution.[35]

Modern-day Religion

[edit]According to 2000 survey, 86.53% of the population of Western Visayas professed Roman Catholicism. Aglipayan (4.01%) and Evangelicals (1.48%) were the next largest groups, while 7.71% identified with other religious affiliations.[71]

The same survey showed that 92% of household populations in Central Visayas were Catholics, followed by Aglipayans (2%) and Evangelicals (1%). The remaining 5% belonged to the United Church of Christ in the Philippines, Iglesia ni Cristo, various Protestant denominations or other religions.[1]

For Eastern Visayas, 93% of the total household population were Catholics, while 12% identified as "Aglipayan", and 1% as "Evangelical". The remaining 5% belonged to other Protestant denominations (including the Iglesia ni Cristo, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and various Baptist churches) or identified with Islam and other religions.[72]

The Tausūg people are excluded in these statistics because they do not self-identify as Visayans. The Tausug are overwhelmingy Muslim and are grouped together with other Muslim ethnic groups of the Philippines as the Moro people.

Festivals

[edit]Visayans are known in the Philippines for their festivities such as the Ati-Atihan, Dinagyang,[73] Pintados-Kasadyaan, Sangyaw, Sinulog festivals. Most Visayan festivals have a strong association with Roman Catholicism despite apparent integration of ancient Hindu-Buddhist-Animist folklore particularly the tradition of dances and the idols in the image of the Child Jesus commonly named as the Santo Niño. The oldest Catholic religious image in the islands still existing today is the Santo Niño de Cebú.

The Sandugo Festival of Tagbilaran, Bohol is a celebration of one of the most significant parts of pre-Philippine history. This festival revolves around the theme of the reenactment of the blood compact between the island's monarch, Datu Sikatuna, and the Spanish explorer, Miguel López de Legazpi, which is known among Filipinos as the Sandugo (lit. unified/one blood). The arrival of the ten Bornean datus as mentioned in the legend of Maragtas is celebrated in Binirayan Festival in Antique.[74]

The MassKara Festival of Bacolod, Negros Occidental explores more on the distinct cultural identity of the city. Since Bacolod is tagged as the City of Smiles due to its fun-loving and enduring people, the city government inaugurated the festival in 1980 after tragedy struck the region.[75][76]

Literature

[edit]Some of the earliest known works were documented by a Spanish Jesuit named Ignacio Francisco Alzina during the Spanish colonial Philippines. Among these literary pieces from ancient Eastern Visayas were kandu, haya, ambahan, kanogon, bikal, balak, siday and awit which are predominantly in Waray. There were also narratives called susmaton and posong. It was also described that theater played a central role in performing poetry, rituals and dances.[77] The Western Visayans also shared nearly the same literary forms with the rest of the islands. Among their pre-Hispanic works were called the bangianay, hurobaton, paktakun, sugidanun and amba. These were all found to be in Old Kinaray-a. Some of the widely known and the only existing literature describing ancient Visayan society are as the Hinilawod and the Maragtas which was in a combination of Kinaray-a and Hiligaynon.[78][79] The Aginid: Bayok sa Atong Tawarik is an epic retelling a portion of ancient Cebu history where the Chola dynasty minor prince Sri Lumay of Sumatra founded and ruled the Rajahnate of Cebu.[80] It also has accounts of Rajah Humabon and Lapu-Lapu.[81]

It was found by Filipino polymath José Rizal in Antonio de Morga's Sucesos delas islas Filipinas that one of the first documented poets in much of pre-Philippines known to Europeans was a Visayan named Karyapa.[82] During the golden age of Philippine languages at the onset of Japanese occupation, numerous Visayan names rose to literary prominence. Acclaimed modern Visayan writers in their respective native languages are Marcel Navarra, the father of modern Cebuano literature, Magdalena Jalandoni, Ramon Muzones, Iluminado Lucente, Francisco Alvardo, Eduardo Makabenta, Norberto Romuáldez, Antonio Abad, Augurio Abeto, Diosdado Alesna, Maragtas S. V. Amante, Epifanio Alfafara, Jose Yap, Leoncio P. Deriada, Conrado Norada, Alex Delos Santos, John Iremil Teodoro and Peter Solis Nery.

Don Ramon Roces of Roces Publishing, Inc. is credited for the promulgation of Visayan languages in publications through Hiligaynon and Bisaya.[83]

Cinema, television and theatre

[edit]Visayan films, particularly Cebuano-language ones, experienced a boom between the 1940s and the 1970s. In the mid 1940s alone, a total of 50 Visayan productions were completed, while nearly 80 movies were filmed in the following decade.[citation needed] This wave of success has been bolstered by Gloria Sevilla, billed as the "Queen of Visayan Movies",[84] who won the prestigious Best Actress award from the 1969 FAMAS for the film Badlis sa Kinabuhi and the 1974 Gimingaw Ako.[85] Caridad Sanchez, Lorna Mirasol, Chanda Romero, Pilar Pilapil and Suzette Ranillo are some of the industry's veterans who gained recognition from working on Visayan films.

The national film and television industries are also supported by actors who have strong Visayan roots such as Joel Torre, Jackie Lou Blanco, Edu Manzano, Manilyn Reynes, Dwight Gaston, Vina Morales, Sheryl Reyes, and Cesar Montano, who starred in the 1999 biographical film Rizal and multi-awarded 2004 movie Panaghoy sa Suba.[86] Younger actors and actress of Visayan origin or ancestry include Isabel Oli, Kim Chiu, Enrique Gil, Shaina Magdayao, Carla Abellana, Erich Gonzales and Matteo Guidicelli.

Award-winning director Peque Gallaga of Bacolod has garnered acclaim from his most successful movie Oro, Plata, Mata which depicted Negros Island and its people during World War II. Among his other works and contributions are classic Shake, Rattle & Roll horror film series, Scorpio Nights and Batang X.

GMA Network's 2011 period drama teleserye Amaya as well as its 2013 series Indio, featured the politics and culture of ancient and colonial Visayan societies, respectively.

Music

[edit]Traditional Visayan folk music were known to many such as Dandansoy originally in Hiligaynon and is now commonly sang in other Bisayan languages. Another, although originally written in Tagalog, is Waray-Waray, which speaks of the common stereotypes and positive characteristics of the Waray people. American jazz singer Eartha Kitt also had a rendition of the song in her live performances.[87] A very popular Filipino Christmas carol Ang Pasko ay Sumapit translated by Levi Celerio to Tagalog was originally a Cebuano song entitled Kasadya Ning Taknaa popularized by Ruben Tagalog.[88]

Contemporary Philippine music was highly influenced and molded through the contributions of many Visayan artists. Many of them are platinum recorder Jose Mari Chan, Pilita Corrales, Dulce, Verni Varga, Susan Fuentes, Jaya and Kuh Ledesma who enjoyed acclaim around the 1960s to the early 1990s. Newer singers are Jed Madela, Sheryn Regis and Sitti Navarro.

Yoyoy Villame, a Boholano, is dubbed as the Father of Filipino novelty songs with his Butsekik as the most popular. Villame often collaborated with fellow singer, Max Surban. Joey Ayala, Grace Nono and Bayang Barrios are some of the front-runners of a branching musical subgenre called Neotraditional which involved traditional Filipino instruments with modern rhythm and melody.

Rock emerged into dominance within the Philippine music scene in the 1980s. Among the bands from Visayas are Urbandub and Junior Kilat. Another subgenre also sprung a few years later called BisRock which is a portmanteau of Bisaya and rock.

Dance

[edit]Ethnic dances from the region are common in any traditional Filipino setting. Curacha or kuratsa (not to be confused with the Zamboangueño dish) is a popular Waray dance. Its Cebuano counterparts are kuradang and la berde.[89] There is the liki from Negros Occidental[90] and the well-known tinikling of Leyte.[91][92] Other Hiligaynon dances are the harito, balitaw, liay, lalong kalong, imbong, inay-inay and binanog.[93]

Visual arts

[edit]The only Boholano and the youngest to receive the National Artist of the Philippines award for visual arts is Napoleon Abueva. He is also tagged as the Father of Modern Philippine Sculpture. Among his works are Kaganapan (1953), the Transfiguration (1979) and the 14 Stations of the Cross around the EDSA Shrine.[94] He is also responsible for the sculpture of the Sandugo monument at Tagbilaran City to give homage to his roots.

A renowned figure in architecture is Leandro Locsin of Silay, Negros Occidental. He was proclaimed as National Artist of the Philippines for architecture in 1990. Locsin worked on many of the buildings in many campuses of the University of the Philippines System. He also designed the main building or the Tanghalang Pambansa of the Cultural Center of the Philippines and the Ayala Tower One & Exchange Plaza housing the Philippine Stock Exchange at Makati.

See also

[edit]- Bisaya (Borneo), a similarly-named ethnic group in Borneo

- Pintados

- Visayas

- Luções

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Timawa

- Malay world

- Bisaya (genus)

- Boxer Codex

- Tagalog people

- Kapampangan people

- Ilocano people

- Ivatan people

- Igorot people

- Pangasinan people

- Bicolano people

- Negrito

- Lumad

- Moro people

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Central Visayas: Three in Every Five Households had Electricity (Results from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing, NSO)". National Statistics Office, Republic of the Philippines. July 15, 2003. Archived from the original on February 21, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Lifshey, A. (2012), The Magellan Fallacy: Globalization and the Emergence of Asian and African Literature in Spanish, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press

- ^ Isorena, Efren B. (2004). "The Visayan Raiders of the China Coast, 1174-1190 AD". Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society. 32 (2): 73–95.

- ^ Frances Antoinette Cruz, Nassef Manabilang Adiong (2020). International Studies in the Philippines Mapping New Frontiers in Theory and Practice. Taylor and Francis. p. 27. ISBN 9780429509391.

- ^ Richard Pearson (2022). Taiwan Archaeology Local Development and Cultural Boundaries in the China Seas. University of Hawaii Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780824893774.

- ^ Jocano, F. Landa (July 31, 2009). Sulod Society: A Study in the Kinship System and Social Organization of a Mountain People of Central Panay. University of the Philippines Press. pp. 23, 24.

- ^ "... and because I know them better, I shall start with the island of Cebu and those adjacent to it, the Pintados. Thus I may speak more at length on matters pertaining to this island of Luzon and its neighboring islands..." BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803, Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583), p. 35.

- ^ Cf. Maria Fuentes Gutierez, Las lenguas de Filipinas en la obra de Lorenzo Hervas y Panduro (1735-1809) in Historia cultural de la lengua española en Filipinas: ayer y hoy, Isaac Donoso Jimenez, ed., Madrid: 2012, Editorial Verbum, pp. 163-164.

- ^ G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, pp. 122-123.

- ^ Cf. Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1911). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 04 of 55 (1493-1803). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 257-260.

- ^ Francisco Colin, S. J., Labora Evangelica de los Obreros de la Campania de Jesus en las Islas Filipinas (Nueva Edicion: Illustrada con copia de notas y documentos para la critica de la Historia General de la Soberania de Espana en Filipinas, Pablo Pastells, S. J., ed.), Barcelona: 1904, Imprenta y Litografia de Henrich y Compañia, p. 31.

- ^ a b Blair, Emma Helen; Robertson, James Alexander (1907). Morga's Philippine Islands. Artur H. Clark Company.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press. pp. 20–27. ISBN 9789715501354.

- ^ Regalado, Felix B.; Quintin, Franco B. (1973). Grino, Eliza U. (ed.). History of Panay. Jaro, Iloilo City: Central Philippine University. p. 514.

- ^ Paredes, Oona (2016). "Rivers of Memory and Oceans of Difference in the Lumad World of Mindanao". TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 4 (Special Issue 2 (Water in Southeast Asia)): 329–349. doi:10.1017/trn.2015.28.

- ^ Alcina, Francisco Ignacio (1668). Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas.

- ^ Bernad, Miguel A. (2001). "Butuan or Limasawa? The site of the first mass in the Philippines: A reexamination of the evidence". Budhi: A Journal of Ideas and Culture. 5 (3): 133–166. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ Bersales, Jobers (February 26, 2009). "One Visayas is here!". Cebu Daily News. Archived from the original on December 16, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ Hermosa, Nath (August 24, 2011). "A Visayan reading of a Luzon artifact". Imprints of Philippine Science. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Nowell, C. E. (1962). "Antonio Pigafetta's account". Magellan's Voyage Around the World. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015008001532. OCLC 347382.

- ^ Medina, A.; Pulumbarit, V. (October 18, 2012). "A Primer: Life and Works of Blessed Pedro Calungsod". Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Mojares, Resil B (1999). The War Against the Americans: Resistance and Collaboration in Cebu, 1899–1906. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-298-6.

- ^ "Aklan". Panubilon. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "A Brief History of Negros Occidental: Pre-Spanish Colonial Period to Present Day". Go Dumaguete!. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ Clavel, Leothiny (1995). "Philippine Revolution in Capiz". Diliman Review. 43 (3–4): 27–28.

- ^ Funtecha, H. F. (May 15, 2009). "The Great Triumvirate of Capiz". The News Today. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "Batas Pambansa Blg. 309". Retrieved September 2, 2021 – via Supreme Court E-Library.

- ^ Funtecha, Henry (May 16, 2007). "The Babaylan-Led Revolt in Igbaong, Antique". The News Today. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ Mateo, G. E. C. (2001). The Philippines: A Story of A Nation. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i at Manoa. hdl:10125/15372.

- ^ Velmonte, J. M. (2009). "Ethnicity and Revolution in Panay". Kasarinlan. 14 (1): 75–96.

- ^ Serag, S. S. C. (1997). The Remnants of the Great Ilonggo Nation. Manila: Rex Book Store.

- ^ Aguilar, F. (2000). "The Republic of Negros". Philippine Studies. 48 (1): 26–52. JSTOR 42634352.

- ^ "Evolution of the Revolution". Malacañan Palace. Republic of the Philippines.

- ^ Zaide, G. F. (1954). The Philippine Revolution. Manila: Modern Book Company.

- ^ a b Aguilar, F. V. (1998). Clash of Spirits: The History of Power and Sugar Planter Hegemony on a Visayan Island. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- ^ Nabong-Cabardo, R. (2002). "A revolution unfolds in Samar victory in Balangiga". In Gotiangco, G. G.; Tan, S. K.; Tubangui, H. R. (eds.). Resistance and Revolution: Philippine Archipelago in Arms. Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts, Committee on Historical Research.

- ^ Presidential Museum and Library (June 11, 2014). "June 12 and the commemoration of Philippine independence".

- ^ McAllister Linn, B. (2000). The Philippine War 1899–1901. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press.

- ^ Mayol, Ador Vincent S. (April 3, 2014). "Feast of San Pedro Calungsod: 'Having a saint from the Visayas is not enough'". Cebu Daily News. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Chee, K. T. (2010). Identity and Ethnic Relations in Southeast Asia: Racializing Chineseness. New York: Springer.

- ^ See, T. A. (1997). The Chinese in the Philippines: Problems and Perspectives. Vol. 2. Manila: Kaisa para sa Kaunlaran, Inc.

- ^ Pinches, Michael (2003). "Restructuring Capitalist Power in the Philippines: Elite Consolidation and Upward Mobility in Producer Services". In Dahles, Heidi; van den Muijzenberg, Otto (eds.). Capital and Knowledge in Asia: Changing Power Relations. Routledge. pp. 64–89. ISBN 9780415304177.

- ^ Tilman, R. O. (1974). "Philippine-Chinese Youth – Today and Tomorrow". In McCarthy, C. J. (ed.). Philippine-Chinese Profile: Essays and Studies. Manila: Pagkakaisa sa Pag-unland.

- ^ Zulueta, J. O. (2007). "I "Speak Chinese, but ...": Code-Switching and Identity Construction Among Chinese-Filipino Youth". Caligrama: Journal of Studies and Researches on Communication, Language, and Media. 3 (2). doi:10.11606/issn.1808-0820.cali.2007.65395.

- ^ "A History of the Philippines by David P. Barrows" Page 147. The few years of Ronquillo's reign were in other ways important. A colony of Spaniards was established at Oton, on the island of Panay, which was given the name of Arévalo (Iloilo).

- ^ Galay-David, Karlo Antonio. "We Who Seek to Settle Problematizing the Mindanao Settler Identity". Davao Today.

- ^ Blanchetti-Revelli, L. (2003). "Moro, Muslim, or Filipino? Cultural Citizenship as Practice and Process". In Rosaldo, R. (ed.). Cultural Citizenship in Island Southeast Asia: Nation and Belonging in the Hinterlands. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 44–75. doi:10.1525/california/9780520227477.003.0003. ISBN 9780520227477.

- ^ a b c Jocano, F. Landa (1958). "The Sulod: A Mountain People In Central Panay, Philippines". Philippine Studies. 6 (4): 401–436. JSTOR 42720408.

- ^ Francia, Luis H. (2013). History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos. Abrams. ISBN 9781468315455.

- ^ Wilcken, Lane (2010). Filipino Tattoos: Ancient to Modern. Schiffer. ISBN 9780764336027.

- ^ Souza, George Bryan; Turley, Jeffrey Scott (2015). The Boxer Codex: Transcription and Translation of an Illustrated Late Sixteenth-Century Spanish Manuscript Concerning the Geography, History and Ethnography of the Pacific, South-east and East Asia. BRILL. pp. 334–335. ISBN 9789004301542.

- ^ Junker, Laura L. (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824864064.

- ^ Umali, Justin (March 3, 2020). "High Culture: The Visayans Before Spanish Colonization Were Badasses". Esquire. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ Glick, Leonard B. (2009). "Real Men: Foreskin Cutting and Male Identity in the Philippines1". Circumcision and Human Rights. pp. 155–174. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9167-4_14. ISBN 978-1-4020-9166-7.

- ^ Zaide, G. F. (2006). T. Storch (ed.). "Filipinos before the Spanish conquest possessed a well-ordered and well-thought-out religion". Religions and Missionaries Around the Pacific, 1500–1900. Hampshire, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- ^ Abueg, E. R.; Bisa, S. P; Cruz, E. G. (1981). Talindaw: Kasaysayan ng Pantikan sa Pilipino paa sa Kolehiyo at Unibersidad. Merriam & Webster, Inc.

- ^ Guillermo, A. R. (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines (3rd ed.). Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press, Inc.

- ^ Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 41.

- ^ Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 133.

- ^ Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 133 and 135.

- ^ Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 135.

- ^ a b Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 131.

- ^ Speaking about the theogony, i.e., genealogy of the local gods of the Visayans, the historian Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino comments on Labaodumgug (Labaw Donggon), who is in the list of these gods, saying that he "is a hero in the ancient time, who was invoked during weddings and in their songs. In Iloilo there was a rock which appear to represent an indigenous man who, with a cane, impales a boat. It was the image or the diwata himself that is being referred to". the actual words of the historian are: "Labaodumgog, heroe de su antegüedad, era invocado en sus casamientos y canciones. En Iloilo había una peña que pretendía representar un indígna que con una caña impalía un barco. Era la imágen ó il mismo dinata d que se trata." Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 42.

- ^ Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo, June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 121-126.

- ^ Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 131.

- ^ Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, pp. 41-42.

- ^ Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 44.

- ^ Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, pp. 44- 45.

- ^ Halili, C. N. (2004). Philippine History. Manila: Rex Bookstore, Inc.

- ^ Tarling, N. (1992). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 1, from Early Times to c. 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Western Visayas: Eight Percent of the Total Population Were From Western Visayas (Results from the 2000 Census of Population Housing, NSO)" (Press release). National Statistics Office, Republic of the Philippines. July 15, 2003. Archived from the original on February 21, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ "Eastern Visayas: Population to Increase by 149 Persons Per Day (Results from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing, NSO)" (Press release). National Statistics Office, Republic of the Philippines. January 17, 2003. Archived from the original on February 21, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University. "The Ati-Atihan and other West Visayan festivals". Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ Tadz Portal; Kitz Y. Elizalde (January 21, 1999). "Antique revives Binirayan festival". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- ^ "Featured Destinations". Philippine Department of Tourism. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012.

- ^ "Why MassKara?". July 24, 2010. Archived from the original on September 1, 2012.

- ^ Sugbo, Victor N. "The Literature of Eastern Visayas". National Commission for Culture and The Arts, Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Deriada, Leoncio P. "Hiligaynon Literature". National Commission for Culture and The Arts, Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ El Cid (December 5, 2009). "Western Visayan Pre-Colonial Literature: A Tapestry of Spoken Stories". Amanuensis. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Abellana, Jovito (1952). Aginid, Bayok sa Atong Tawarik. Cebu Normal University Museum.

- ^ Valeros, M. A. E. (September 13, 2009). "The Aginid". The Freeman. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Josephil Saraspe (April 3, 2009). "Visayan Poetry and Literature". Wits and Spirits. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Lent, John A. (2014). "Philippine Komiks: 1928 to the Present". Southeast Asian Cartoon Art: History, Trends and Problems. McFarland and Company. pp. 39–74. ISBN 9780786475575.

- ^ Protacio, R. R. (2009). "Gloria Sevilla: The queen of Visayan movie land".

- ^ "The 50's: Golden Age of Philippine Cinema". Archived from the original on February 9, 2013.

- ^ Javier-Alfonso, G. (n.d.). "Cesar Montano, a Superior Story Teller". Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Ocampo, A. (January 7, 2009). "Eartha Kitt's Philippine Connection". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012.

- ^ Guerrero, A. M. (November 10, 2008). "Let Us Now Praise Famous Visayans". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ "Visayan Dances". SEAsite. Northern Illinois University.

- ^ "Liki (Philippines)" (PDF). 1968 – via folkdance.com.

- ^ "Researchers Probe Possible Origin of 'Tinikling' Folkdance in Leyte". Philippine Information Agency. August 28, 2006. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Henkel, Steven A. "Tinikling Ideas". Homepage of Steven A. Henkel, Ph.D. Professor of Physical Education Bethel University † St. Paul, MN. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ Funtecha, H. F. (June 9, 2006). "What Ilonggo Culture Is". The News Today Online Edition.

- ^ "Napoleon V. Abueva, The National Artist". The Oblation. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013.

External links

[edit]- Visayan Languages, filipinolanguages.com.

- Visayan, everyculture.com.

- The issues on the use of the word 'Bisaya' by Henry Funtecha, PhD The News Today. August 28, 2009, Iloilo City, Philippines.