China Clipper

| China Clipper | |

|---|---|

Martin M-130 NC14716 China Clipper | |

| General information | |

| Type | Martin M-130 |

| Manufacturer | Glenn L. Martin Company |

| Owners | Pan American Airways |

| Registration | NC14716 |

| History | |

| First flight | December 1934 |

| Last flight | 8 January 1945 |

| Fate | Crashed on approach due to excessive speed and rate of descent (CFIT) |

China Clipper (NC14716) was the first of three Martin M-130 four-engine flying boats built for Pan American Airways and was used to inaugurate the first commercial transpacific airmail service from San Francisco to Manila on November 22, 1935.[1] Built at a cost of $417,000 by the Glenn L. Martin Company in Baltimore, Maryland, it was delivered to Pan Am on October 9, 1935.[2] It was one of the largest airplanes of its time.

On November 22, 1935, it took off from Alameda, California on commission to deliver the first airmail cargo across the Pacific Ocean.[3] Although its inaugural flight plan called for the China Clipper to fly over the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge (still under construction at the time), upon take-off the pilot realized the plane would not clear the structure, and was forced to fly narrowly under instead[citation needed]. On November 29, the airplane reached its destination, Manila, after traveling via Honolulu, Midway Island, Wake Island, and Sumay, Guam, and delivered over 110,000 pieces of mail. The crew for this flight included Edwin C. Musick as pilot and Fred Noonan as navigator.[4] The inauguration of ocean airmail service and commercial air flight across the Pacific was a significant event for both California and the world. Its departure point is California Historical Landmark #968 and can be found in Naval Air Station Alameda.[5]

Aircraft

[edit]

Although each clipper that joined the Pan American fleet to serve on their Trans-Pacific routes was given an individual name, collectively they were known as the China Clippers.

Although a Sikorsky S-42 flying boat was used on the initial proving flights, it had insufficient range to carry passengers along the route. Consequently, the passenger service was started with Martin M-130 flying boats:[6]

- China Clipper (NC-14716) October 1935

- Philippine Clipper (NC-14715) November 1935

- Hawaii Clipper (NC-14714) March 1936

Later the larger Boeing 314 Clipper flying boats were assigned to the route:[citation needed]

- Honolulu Clipper (NC-18601) January 1939

- California Clipper (NC-18602) January 1939

- Pacific Clipper (NC-18609(A)) May 1941

Additional clippers were assigned to the Trans-Atlantic and South American routes operated by Pan-American.

That China Clipper's wingspan was 130 feet and it weighed 52,000 pounds. It was powered by four Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp 14-cylinder radial engines and could achieve a maximum speed of 180mph. The aircraft had a maximum range of 3,200 miles, with a cruising ceiling of 17,000 feet and could carry 18 passengers on overnight trips, or 46 passengers on single day trips.[7]

The clippers were, for all practical purposes, luxury flying hotels, with sleeping accommodation, dining rooms and leisure facilities in addition to the usual aircraft seating. On early flights, the crew outnumbered the passengers. As a result, the price of a return air ticket from San Francisco to Honolulu was $1700[8] (equivalent to $36,000 in 2023)[9]. In comparison, a brand-new Plymouth automobile cost about $600 in the late 1930s.

Airmail service

[edit]

Considerable effort was put into preparing for the inauguration of the first Trans-Pacific airmail flight. In San Francisco the celebrations for the inaugural trans-Pacific airmail flight included fireworks, while a band played a Sousa march. Eleven days prior, Musick had flown the China Clipper from the Glenn L. Martin factory in Middle River, Maryland to California for the inaugural event. Ships docked in the bay to observe the historic event, sounding their whistles and sirens in tribute. It was estimated that up to a hundred thousand people watched from the various shores of San Francisco Bay. Several speeches were made by various public figures after which there was a ceremonial loading of the numerous mail bags. Musick's sailing orders were publicly delivered by his boss, Juan Trippe, while the entire event was broadcast by CBS and NBC radio and also transmitted on seven foreign networks.[10]

The relatively short range of the aircraft meant that hotel, catering, docking, repair, road and radio facilities had to be put in place at the intermediate stops along the route, particularly on the virtually uninhabited islands of Wake and Midway. Nearly a half a million miles were flown along the route before any paying passengers were carried.[11]

The China Clipper was the first commercial aircraft to establish a regular airmail route from the United States across the Pacific Ocean. On its inaugural airmail flight the China Clipper took off from Alameda, California, on November 22, 1935, making its way to Manila via Honolulu, Midway Island, Wake Island, and Guam over the course of one week. All stops were chosen on the basis that were links in an “all-American” flag route, i.e. countries friendly with the United States.[7]

There were no passengers, only crew-members aboard the first airmail flight. The payload consisted of 111,000 envelopes weighing approximately 2,000 pounds, making it the largest mail shipment ever taken on board an airplane. Prior to the clipper’s departure, the post office, which anticipated only a third of the final total volume, continued to bring in more plane loads of mail from across the country. In San Francisco some 100 postal clerks were kept busy preparing the tens of thousands of letters in preparation for their delivery aboard the Clipper. The payload of mail was nearly all philatelic, consisting of envelopes prepared by collectors who wanted an example of mail flown on the “first flight”. To accommodate the unexpected volume of mail the furnishings onboard intended for passengers were removed to make room for the mail many dozens of mail pouches.[7]

The China Clipper arrived in Manila on November 29, 1935, eight thousand miles away from San Francisco, making prior stops at Honolulu, Midway Island, Wake Island and Guam. Not counting the hold-over time spent in the several ports along the route, the actual flying time of the aircraft was 59 hours and 48 minutes. The same voyage by the fastest steamship of the time would have taken more than two weeks.[7]

Following the inaugural flight over the Pacific Ocean, the China Clipper's sister ships, the Philippine Clipper and Hawaii Clipper, also of the same model, carried mail and cargo back and forth across the Pacific. By October 1936, points along the route were finally ready to accommodate passenger service.[12]

In January 22, 2024, Emmanuel Calairo, Chairperson of the National Historical Commission in the presence of MaryKay Carlson, the US Ambassador to the Philippines and Commodore Marco Tronqued, unveiled a historical marker at the Manila Yacht Club, honoring the arrival of China Clipper to the Philippines in 1935 (in the presence of MaryKay Carlson, the US Ambassador to the Philippines and Commodore Marco Tronqued).[13][14]

World War II

[edit]The China Clipper was painted olive drab with a large American flag painted below the cockpit.[15] The China Clipper was referred to as "Sweet Sixteen".[16][17] The "Sixteen" is a reference to the aircraft's registration number NC14716.

Crash

[edit]

The China Clipper remained in Pan Am service until January 8, 1945, when it was destroyed in a crash in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. Flight 161 had started at Miami bound for Leopoldville in the Belgian Congo, making its first stop to refuel at Puerto Rico before flying on to Port-of-Spain. After one missed approach, on the second approach to land it came down too low and hit the water at a high speed and nose-down a mile-and-a-quarter short of its intended landing area. The impact broke the hull in two which quickly flooded and sank. Twenty-three passengers and crew were killed; there were seven survivors including Captain C.A. Goyette, Pilot-in-Command for the flight, and Captain L.W. Cramer, First Officer, who was flying the plane from the left seat when it crashed.[18]

On April 24, 1946, the Civil Aeronautics Board released its accident investigation report with the following findings "upon the basis of all available evidence":

- The carrier, aircraft and pilots had proper certificates.

- Captain Cramer, having very limited flight time in the aircraft, was at the controls with Captain Goyette acting in a supervisory capacity.

- Conditions of weather and water surface within the vicinity of Port-of-Spain were satisfactory for a safe approach and landing.

- The plane first contacted the water at a higher-than-normal landing speed, and in a nose-low attitude.

- The crash occurred at a point one-and-a-quarter miles short of the intended landing area.

- Forces created by the speeds of the plane on its contact with the water and the excessive nose-down-attitude caused failure of the hull bottom and its structure resulting in rapid submersion of the aircraft.

- Landing of the aircraft in the attitude indicated, under the then-existing conditions of water surface and weather, was due to Cramer's having misjudged his true altitude and his failure to correct his attitude for a normal landing.

- At the time of the accident, Captain Cramer was not wearing eyeglasses as required by his pilot certificate.

- Captain Goyette, in command of the aircraft and with full knowledge of Cramer's limited experience in the Martin M-130, failed to exercise sufficient supervision of the landing.

- Probable cause: On the basis of the above findings, the board determined that the probable cause of this accident was: (1) First Officer Cramer's failure to realize his proximity to the water and to correct his attitude for a normal landing and, (2) the lack of adequate supervision by the captain during the landing resulting in the inadvertent flight into the water in excess of normal landing speed and in a nose-down attitude.[19]

Legacy

[edit]

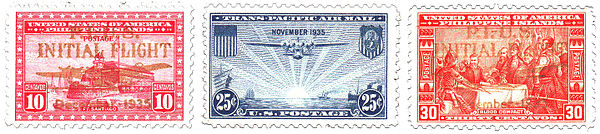

Both the United States and Philippine Islands issued stamps for air mail carried on the first flights in each direction of PAA's Transpacific China Clipper service between San Francisco and Manila (November 22 – December 6, 1935)

First National Pictures released the movie China Clipper in 1936. It told a thinly disguised bio of the life of Juan Trippe during the founding of PanAm. The film made use of much documentary footage of the actual airplane, as well as aerial photography created specifically for the production. It was also one of Humphrey Bogart's early roles.[20][21]

Footage of the China Clipper, and/or possibly other M-130s loading and taking off from Alameda, is included in the 1937 comedy film Fly-Away Baby and the 1939 adventure film Secret Service of the Air.[citation needed]

The China Clipper is also a significant setting in the contemporaneous radio serial Speed Gibson of the International Secret Police (1937–1939).[citation needed] More recently, it was referenced in the Monkees song "Zilch" from their 1967 album Headquarters. Davy Jones can be heard repeating "China Clipper calling Alameda" in that track.

The flying boats and Treasure Island, San Francisco were featured by Huell Howser in California's Gold Episode 906.[22]

China Clipper II

[edit]

In 1985, Pan Am resurrected the "China Clipper" aircraft name onto its new Boeing 747-212B registered N723PA, which was named "China Clipper II" to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the China Clipper Flight. On November 22, 1985, the China Clipper II began its flight across the Pacific to retrace the original route of the first China Clipper Flight.[23][24] The flight departed from San Francisco on November 22, 1985, and made several stop flight following the original China Clipper flight route, such as Honolulu, Wake Island, Guam and all the way to Manila with its final destination to Bali, which was a new route that was not included in the original itinerary. Pan Am also made several advertisements and television commercials to promote the new China Clipper II plane which shows the original China Clipper Martin M-130 plane and also the new China Clipper II Boeing 747-212B aircraft and was aired in several countries as part of Pan Am promotion to commemorate China Clipper 50th Anniversary Flight.[24][23]

See also

[edit]- Hawaii Clipper disappeared in 1938

- Pan Am Flight 1104, crash of Philippine Clipper in 1943

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Video: California, 1959/04/30 (1959). Universal Newsreel. 1959. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ Volny, Peter China Clipper 75th Anniversary Commemorative Flight Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine The Airport Journal, April, 2008

- ^ "China Clipper's Inaugural Flight from San Francisco to Manila" San Francisco Examiner, November 26, 1935

- ^ along with First Officer R. O. D. Sullivan, C. D. Wright, Victor Wright, George King, and William Jarboe. Musick was a famous pilot of the time. Fred Noonan went on to work with Amelia Earhart and disappeared along with her over the western Pacific Ocean in 1937.

- ^ flyingclippers.com M130

- ^ clipperflyingboats.com china clipper

- ^ a b c d Smithsonian National postal museum, Essay

- ^ "Pan American Airways wins Collier Trophy for Pacific Plane Service" Life. August 23, 1937. pp. 35–41.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Gandt, 1991, p. 2

- ^ "Flying the China Clippers". Popular Mechanics. April 1938. pp. 500–503.

- ^ Romanowski, 2014, National Flight and Space Museum, Essay

- ^ Lee, Izzy (January 23, 2024). "Marker commemorating Pan Am China Clipper arrival unveiled at Manila Yacht Club". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs.

- ^ Rodriguez, Feliciano (Jan 12, 2024). "Wings of History: Honoring the Pan Am China Clipper's landmark arrival in the Philippines". Manila Bulletin.

- ^ Howard Waldorf (March 1944). "China Clipper". Flying: 25.

- ^ Gandt, 1991, pp. 38-39

- ^ Taylor, Barry: Pan American's Ocean Clippers, page 112. Aero, an imprint of Tab Books, McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1991.

- ^ Aviation Safety Network Accident description entry for Pan American Airways "China Clipper" NC14716 January 8, 1945 Aviation Safety Foundation

- ^ CAB Accident Investigation Report (Pan American Flight 161) Docket No. SA-99, File No. 98-45, Adopted April 19, 1945, Released April 24, 1945 (PDF) (Report). Civil Aeronautics Board. 1946-04-24. Retrieved 2013-07-15.[permanent dead link]

- ^ China Clipper

- ^ "China Clipper" (1936) film footage from movie

- ^ "China Clipper – California's Gold (906) – Huell Howser Archives at Chapman University". 8 January 1998.

- ^ a b "AirHistory.net - "China Clipper II" named aircraft photos". www.airhistory.net. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ^ a b Baldwin, James Patrick (2021). Pan American World Airways - Images of a Great Airline Second Edition (2nd ed.). English: Independently published. ISBN 979-8752615184.

Bibliography

- Pope, Nancy (2014). "The China Clipper". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- Gandt, Robert L (1991). China Clipper : the age of the great flying boats. Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, Md. ISBN 978-0-87021-2093.

- Romanowski, David (2014). "The First Transpacific Passenger Flight". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- "Alameda". California Historical Landmarks. Office of Historical Preservation. Retrieved 2005-08-25.

- Cohen, Stan Wings to the Orient, Pan-Am Clipper Planes 1935–1945 Pictorial Histories.

- "Transpacific" Time, December 2, 1935

- Accident description at Air Safety Network

External links

[edit]- China Clipper – The Martin 130

- Pan American Airways Clippers 1931–1936

- A visit to the former China Clipper base on Treasure Island, San Francisco

- "China Clipper is Giant of Pacific Air Fleet" Popular Mechanics, January 1936

- Final accident report of the Trinidad crash from the Civil Aeronautics Board (PDF)

- Pan Am

- Pan Am accidents and incidents

- Individual aircraft

- Martin aircraft

- Alameda, California

- Aviation accidents and incidents in Trinidad and Tobago

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 1945

- Airliner accidents and incidents involving controlled flight into terrain

- 1945 in Trinidad and Tobago

- January 1945 events in North America