Maximilian I of Mexico

| Maximilian I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Official portrait as emperor of México by Albert Gräfle, 1865 | |||||

| Emperor of Mexico | |||||

| Reign | 10 April 1864 – 19 June 1867[1] | ||||

| Predecessor | Monarchy established (Benito Juárez, as President of the Republic) | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished (Benito Juárez, as President of the Republic) | ||||

| Prime ministers | |||||

| Born | Archduke Maximilian of Austria 6 July 1832 Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, Austrian Empire | ||||

| Died | 19 June 1867 (aged 34) Cerro de las Campanas, Santiago de Querétaro, Restored Republic | ||||

| Burial | 18 January 1868 Imperial Crypt, Vienna, Austria | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| |||||

| House | Habsburg-Lorraine | ||||

| Father | Archduke Franz Karl of Austria | ||||

| Mother | Princess Sophie of Bavaria | ||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Maximilian I (Spanish: Fernando Maximiliano José María de Habsburgo-Lorena; German: Ferdinand Maximilian Josef Maria von Habsburg-Lothringen; 6 July 1832 – 19 June 1867) was an Austrian archduke who became emperor of the Second Mexican Empire from 10 April 1864 until his execution by the Mexican Republic on 19 June 1867.

A member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, Maximilian was the younger brother of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. Prior to his becoming Emperor of Mexico, he was commander-in-chief of the small Imperial Austrian Navy and briefly the Austrian viceroy of Lombardy–Venetia, but was removed by the emperor. Two years before his dismissal, he briefly met with French emperor Napoleon III in Paris, where he was approached by conservative Mexican monarchists seeking a European royal to rule Mexico.[2] Initially Maximilian was not interested, but following his dismissal as viceroy, the Mexican monarchists' plan was far more appealing to him.

Since Maximilian was a descendant of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Spain when the Spaniards conquered the Aztecs (1519–21) and first brought Mexico into the Spanish Empire, a status it held until the Mexican independence in 1821, Maximilian seemed a perfect candidate for the conservatives' plans for monarchy in Mexico.[3] Maximilian was interested in assuming the throne, but only with guarantees of French support. Mexican conservatives did not take sufficient account of Maximilian's embrace of liberalism, and Maximilian failed to understand he would be viewed as a foreign outsider.[4] When Maximilian was first mentioned as a possible emperor of Mexico, the idea seemed farfetched, but circumstances changed and made it viable. His tenure as emperor was just three years, ending with his execution by firing squad by forces of the Restored Republic on 19 June 1867.

Political conflicts in Mexico in the 1850s between conservative and liberal factions were domestic disputes initially, but the conservatives' loss on the battlefield to the liberal regime during a three-year civil war (1858–61) meant conservatives sought ways to return to power with outside allies, opening a path for France under Napoleon III to intervene in Mexico and set up a puppet regime with conservative Mexican support. When the liberal government of Mexican President Benito Juárez suspended payment on foreign debts in 1861, there was an opening for European powers to intervene militarily in Mexico. The intention of the French and Mexican conservatives was for regime change to oust the liberals, backed by the power of the French army. Mexican monarchists sought a European head of state and, with the brokering of Napoleon III, Maximilian was invited to establish what would come to be known as the Second Mexican Empire. With a pledge of French military support and at the formal invitation of a Mexican delegation, Maximilian accepted the crown of Mexico on 10 April 1864 following a bogus referendum in Mexico that purportedly showed the Mexican people backed him.[5]

Maximilian's hold on power in Mexico was shaky from the beginning. Rather than enacting policies that would return power to Mexican conservatives, Maximilian instead sought to implement liberal policies, losing him his domestic conservative backers. Internationally, his legitimacy as ruler was in doubt since the United States continued to recognize Benito Juárez as the legal head of state rather than Emperor Maximilian. The U.S. saw the French invasion as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine, but the U.S. was unable to intervene politically due to the American Civil War (1861–1865). With the end of the American Civil War in 1865, the United States began providing material aid to Juárez's republican forces. In the face of a renewed U.S. interest in enforcing the Monroe Doctrine, under orders by Napoleon III, the French armies that had propped up Maximilian's regime began withdrawing from Mexico in 1866. With no popular support and republican forces in the ascendant, Maximilian's monarchy collapsed. Maximilian was captured in Querétaro. He was tried and executed by the restored Republican government alongside his generals Miguel Miramón, a former President of Mexico, and Tomás Mejía Camacho in June 1867.[6] His death marked the end of monarchism as a major force in Mexico. In reassessments of his brief rule, he is portrayed in Mexican history less as the villain of nationalist, republican history and more as a liberal in Mexico, along with Presidents of the Republic Juárez, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, and Porfirio Díaz.[7]

Early life

[edit]Maximilian was born on 6 July 1832 in the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, capital of the Austrian Empire.[8][9] He was baptized the following day as Ferdinand Maximilian Josef Maria. The first name honored his godfather and paternal uncle, the future Emperor Ferdinand I, and the second honored his late maternal grandfather, Maximilian I Joseph, King of Bavaria.[10][11] His father was Archduke Franz Karl, the second surviving son of Emperor Francis I, during whose reign he was born. Maximilian was thus a member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine.[12] His mother was Princess Sophie of Bavaria, a member of the House of Wittelsbach.[13] Intelligent, ambitious and strong-willed, Sophie had little in common with her husband, whom historian Richard O'Conner characterized as "an amiably dim fellow whose main interest in life was consuming bowls of dumplings drenched in gravy".[14] Despite their different personalities, the marriage was fruitful, and after four miscarriages, four sons – including Maximilian – would reach adulthood.[15] Rumors at the court alleged that Maximilian was the product of an extramarital affair between his mother and Napoleon II, Duke of Reichstadt.[16] The existence of an illicit affair between Sophie and the duke, and any possibility that Maximilian was conceived from such a union, are dubious.[A]

Maximilian's upbringing was closely supervised. Until his sixth birthday, he was cared for by Baroness Louise von Sturmfeder, who was his aja (then rendered "nurse", now nanny). His education was then entrusted to a tutor.[17] Most of Maximilian's day was spent in study. The hours per week of classes steadily increased from 32 at age seven to 55 by the time he was 17.[18] The disciplines were diverse, ranging from history, geography, law and technology, to languages, military studies, fencing and diplomacy.[18] From an early age, Maximilian tried to surpass his older brother Franz Joseph in everything, attempting to prove to all that he was the better qualified of the two and thus deserving of more than second-place status,[19] but with primogeniture, Maximilian was destined for secondary status.

The highly restrictive environment of the Austrian court was not enough to repress Maximilian's natural openness. He was joyful, highly charismatic, and able to captivate those around him with ease. Although he was a charming boy, he was also undisciplined.[20] He mocked his teachers and was often the instigator of pranks – including even his uncle, the emperor, among his victims.[21] His attempts to outshine his older brother and his ability to charm opened a rift between himself and the aloof and self-contained Franz Joseph that widened as years passed, and their close relationship in childhood would be all but forgotten.[19]

During revolutionary unrest in Europe in 1848, Emperor Ferdinand abdicated in favor of Maximilian's older brother Franz Joseph.[22][23] Maximilian accompanied his brother on campaigns to put down rebellions throughout the empire.[24][23] Only in 1849 would the revolution be stamped out in Austria, with hundreds of rebels executed and thousands imprisoned. Maximilian was horrified at what he regarded as senseless brutality and openly complained about it. He would later remark, "We call our age the Age of Enlightenment, but there are cities in Europe where, in the future, men will look back in horror and amazement at the injustice of tribunals, which in a spirit of vengeance condemned to death those whose only crime lay in wanting something different to the arbitrary rule of governments which placed themselves above the law."[25][26]

At a court ball in Vienna, Maximilian met and fell in love with a young Moldavian noblewoman, Viktoria Keșco (1835–1856), paternal aunt of the future Queen of Serbia. But the match was impossible for Archduke Maximilian since her family was Orthodox and did not belong to the family reigning or former reigning monarchs. When their romance was discovered, her father Ioan Keșco (1809–1863), who served as Russian Marshal of Nobility in Bessarabia, quickly sent her back home and forcibly married her off to her longtime admirer, local rich nobleman of Greek descent, Alexander Dimitrievich Inglezi (1826–1903), son of Dimitri Spiridonovich Inglezi (1771–1846).[27][28][29]

Years in the Imperial Austrian Navy

[edit]

Not destined to rule, Maximilian entered military service, training in the small Imperial Austrian Navy. He displayed zeal in his naval career and his direct link with Emperor Franz Joseph enabled the diversion of resources to what had previously been a neglected service.[30]

Maximilian embarked on the corvette Vulkan, for a brief cruise through Greece. In October 1850, he became a navy lieutenant. At the beginning of 1851, he embarked on another much more distant cruise on board the SMS Novara. He enjoyed that voyage so much that he anticipated in his diary "I shall fulfill one of my most beloved dreams, a voyage by sea. I depart with my memories of my beloved Austrian homeland in a very emotional moment for me."[31]

This voyage took him to Lisbon, where he met the princess Maria Amélia of Braganza, daughter of the late Brazilian Emperor Pedro I. She was described as beautiful, pious, clever, and of a refined education.[32] The pair fell in love. His brother Franz Joseph and his mother approved of a prospective marriage between them. Unfortunately, in February 1852, Maria Amélia contracted scarlet fever. Her health worsened over the months, developing tuberculosis. Her doctors advised her to leave Lisbon and go to Madeira, where she arrived in August 1852. At the end of November, she had lost hope of ever recovering her health. [33] Maria Amélia died on February 4, 1853, which deeply shocked Maximilian. [34][35]

Other travels in this era included Italy, Spain, Madeira, Tangiers, and Algeria. He visited Beirut, Palestine, and Egypt.[36] During his visit to Spain in 1854, he visited the tombs of his ancestors Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabel I of Castile in Granada.[37] Later travels took him to the Empire of Brazil. In an 1859 letter to his father-in-law King Leopold I of Belgium he wrote "It seems to me like a legend that I am the first descendant of Ferdinand and Isabela who since early childhood has thought it his mission to tread on the continent that has attained such gigantic importance for the fortunes of humanity."[38]

Maximilian learned to command sailors and received a solid education regarding the technical aspects of navigation. On 10 September 1854, he was named Commander-in-Chief of the Austrian Navy and was granted the rank of counter admiral. As commander-in-chief, Maximilian carried out several reforms to modernize the naval forces. He was instrumental in creating the naval ports at Trieste and Pola (now Pula), as well as the battle fleet with which Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff would later secure his victories. He was however criticized for diverting massive funds to ship building from the training, sea going experience, and morale of sailors.[39] He also initiated a large-scale scientific expedition (1857–1859).

At the end of 1855, he sought refuge for his ship in the Gulf of Trieste during poor sailing weather. He was impressed enough to immediately consider building a residence there, a goal which he actually carried out in March 1856, when he began construction of what would later be called Miramare Castle, located near the city of Trieste.

At end of the Crimean War in March 1856 that brought a period of peace to Europe, Maximilian traveled to Paris to meet Emperor of the French, Napoleon III and his wife the Empress Eugénie.[40] There he also met Mexican conservatives, who would later prove to be decisive in Maximilian's life. The Archduke would write about this initial meeting in his diary "although the emperor lacks the genius of his famous uncle, he retains fortunately for France, a grand personality. He stands tall over the century and shall surely leave his mark on it."[41]

Marriage to Charlotte of Belgium, personal life, and family remnants

[edit]

In May 1856, Franz Joseph asked Maximilian to return from Paris to Vienna, stopping on the way at Brussels, in order to visit the King of the Belgians, Leopold I. On 30 May 1856, he arrived in Belgium where he was received by Prince Philippe, younger son of King Leopold. He was accompanied by the Belgian princes, visiting the cities of Tournai, Kortrijk, Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, and Charleroi. [42] In Brussels, Maximilian met the only daughter of the king and the late queen Louise of Orleans, Charlotte of Belgium, and romance blossomed. [43] Leopold I, upon becoming aware of the couple's feelings advised Maximilian to propose. From the Belgian viewpoint, the marriage was highly advantageous, since the nation was newly established and could benefit from ties to the Great Powers. Having been unlucky in love twice before, Maximilian's marriage to the daughter of a reigning European monarch was suitable and would seem to be a happy conclusion to his bachelorhood. Maximilian proposed and was welcomed into the Belgian Court. He later remarked on the contrast of the Belgian Palace of Laeken to the splendor of the Imperial Viennese royal residences,[42] not surprising since Belgium was but a small and new kingdom.

Prince George of Saxony, who previously had been rejected by Charlotte, warned Leopold I of the "calculating character of the Viennese archduke." [44] The son of Leopold I, the Duke of Brabant, and future Leopold II, in contrast, wrote to Queen Victoria, who was Charlotte's cousin, "Max is a youth filled with ingenuity, knowledge, talent and kindness."

The engagement was formally concluded on 23 December 1856. On 27 July 1857 Maximilian and Charlotte were married in the Royal Palace of Brussels. Distinguished European royals attended the ceremony, including the first cousin of Charlotte and husband of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert. The marriage also enhanced the prestige of the newly established Belgian dynasty as the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha once more found itself allied with the powerful House of Habsburg. [45]

The marriage was not fruitful, producing no children. However, when they were Emperor and Empress of Mexico, they adopted on 9 September 1865 Agustín de Iturbide y Green and his cousin Salvador de Iturbide y Marzán, both grandsons of Agustín de Iturbide, who had briefly reigned as emperor of the First Mexican Empire. Agustin's mother, Alicia Iturbide, an American who was born Alice Green, agreed to give up her child. Soon after, she changed her mind and sent messages to Maximilian to renounce the adoption contract, but she was simply deported from Mexico without her child.[46] Agustín and his cousin were granted the title Prince de Iturbide and the style of Highness by an imperial decree of 16 September 1865, and were ranked next in line after the reigning family.[47] In October 1866, as the Empire began to falter, Maximilian wrote to Alice Iturbide that he was returning her son, Agustín, to her care."[48]

One biographer claims that Maximilian took a mistress in Mexico.[49] Historian Enrique Krauze suggests that Maximilian was rendered sterile due to venereal disease contracted from a Brazilian woman when he spent time in the country following his dismissal as viceroy.[50] However, another biographer contends that not only did Maximilian have a secret entry way in his Cuernavaca residence, allowing him to discreetly have encounters with women, but that Maximilian fathered a child by a Mexican woman in Cuernavaca, Concepción Sedano y Leguizano, who died shortly after Maximilian's execution. Unacknowledged as the emperor's offspring, the boy was allegedly taken to Paris and educated with funds by a Mexican ex-patriate there. During World War I, he was living in Spain, where he was recruited by German intelligence. He was arrested as a traitor by the French and executed by firing squad in 1917. According to the biographer's account, citing no sources in his publication, the charge read out at his execution began "Sedano, son of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico."[51]

Since Maximilian and Carlota had no offspring, there are no direct descendants. However, today members of the House of Habsburg consider Maximilian an important ancestor.[citation needed] But in terms of the Mexican political reality, they are not in the spotlight. The nearest living agnatic relative to Maximilian is the head of the Habsburg family, Karl von Habsburg,[52] and members of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine still reside in Mexico, among them Carlos Felipe de Habsburgo, the first male of the former ruling house to be born in the country.[53] Carlos Felipe is an academic who has given many interviews, conferences, and presentations regarding his family's history, Maximilian and Carlota, and the Second Mexican Empire.[54][55]

Viceroy of Lombardy-Venetia, 1857–59

[edit]

On 28 February 1857, Franz Joseph named Maximilian as viceroy of Lombardy-Venetia, an Italian-speaking region of the empire.[56] On 6 September 1857, Maximilian and Charlotte made their entrance to the capital Milan. During their stay there the couple lived at the Royal Palace of Milan and occasionally resided at the Royal Villa of Monza.[57] As viceroy, Maximilian lived as a sovereign surrounded by an imposing court of chamberlains and servants.[58] During his two years as viceroy, Maximilian continued the construction of Miramar Castle, which would not be finished until three years later. Charlotte's royal dowry aided in the construction. Her brother Leopold would remark in his diary that "the construction of that palace amounts to endless madness."[59]

Maximilian worked on developing the imperial navy, and he organized the expedition of the ship Novara, which would turn out to be the first circumnavigation of the globe conducted by the Austrian Empire, a scientific expedition, which lasted more than two years from 1857 to 1859, and which involved the participation of many Viennese intellectuals. [60] Politically, the Archduke was strongly influenced by nineteenth-century liberalism, generally not a political position that those of royal blood adhered to. The appointment of the young progressive Maximilian to the office of viceroy was made in response to the growing discontent of the Italian population with the rule of the older Joseph Radetzky von Radetz. The appointment of an Archduke, indeed the Emperor's own brother, was also intended to encourage the local population's personal loyalty to the House of Habsburg.[61]

Charlotte made efforts to win over her subjects, speaking Italian, visiting charitable institutions, inaugurating schools, and dressing in native Lombard dress. [62] On Easter 1858, Maximilian and Charlotte sailed down the Grand Canal of Venice in ceremonial dress. [63] Despite their efforts, anti-Austrian sentiment continued to spread rapidly throughout the Italian population. [56]

Maximilian's efforts in administering the province included a revision of the tax registry, a more equitable distribution of tax revenue, the establishment of medical districts, dredging the Venetian canals, expanding the port of Cuomo, draining swamps to put a stop to malaria, fertilization projects and the irrigation of the plains of Friuli. There was also a series of urban development projects. The Riva degli Schiavoni was extended to the royal gardens of Venice, while in Milan, the avenues gained priority, the Piazza del Duomo was widened, and a new piazza was built between the Teatro alla Scala and the Palazzo Marino. The Biblioteca Ambrosiana library was also restored. [64]

The British minister of foreign relations wrote in 1859 that "the administration of the provinces of Lombardy-Venetia were directed by the Archduke Maximilian with great talent, and both a liberal and conciliatory spirit." [65]

Dismissal as viceroy

[edit]

Maximilian's tenure as viceroy was short-lived, lasting only two years during a period of rising local tensions. Although holding title of viceroy, his jurisdiction did not fully extend over the Austrian garrison, which was opposed to any sort of liberal reforms. Maximilian went to Vienna in April 1858 to ask his brother the emperor to grant him both military and administrative jurisdiction, while continuing a policy of concessions. Franz Joseph rejected the appeal. [56] That left Maximilian with only the limited role of prefect of police while tensions with Piedmont were rising. On 3 January 1859, for security reasons, Carlota was asked to return to Miramar, and she sent her valuables out of Lombardy-Venetia. Only while safe in the royal Palace of Milan did she share her concerns with her mother-in-law Sophie. [66]

In February 1859, the Austrian military cracked down, making numerous arrests in Milan and Venice. The prisoners came from the upper classes and were transported to Mantua and various prisons throughout the realm. The city of Brescia was occupied by militia, while several battalions were camped in Piacenza, and on the shores of the River Po. Maximilian hoped to moderate the severe dispositions of General Ferenc Gyulay. Maximilian had just received permission from his brother to open the private law schools in Pavia and Padua. In March 1859, there were incidents between the Milanese police and the Veronese public. In Pavia, one of the cities governed by Maximilian, Austria created a veritable state of military occupation. The Italian situation was becoming critical, and order could no longer be maintained without troops.[67]

The Austrian archduke's conciliatory efforts ultimately fell apart when his various projects for improving the wellbeing of the Italian public were shut down. Franz Joseph was intent on preventing any concessions to the populace. The emperor considered Maximilian too liberal and generous with the rebellious Italian population. [68] Franz Joseph relieved his brother of his post as viceroy on 10 April 1859. [69]

In Italy, news of Maximilian's dismissal was received with sarcastic enthusiasm by statesmen there. A pivotal figure in the movement for Italian unification, the Count of Cavour, who declared that

In Lombardy, our worst enemy...was the Archduke Maximilian; young, active, enterprising, who dedicated himself completely to the difficult task of winning over the Milanese, and who was about to triumph in it. The Lombardian provinces had never been so prosperous or well administered. Thank God that the good government of Vienna intervened, and as usual, took advantage of the opportunity to commit a blunder, an impudent act, one most fatal to Austria, but most advantageous to Piedmont...Lombardy shall now fall into our grasp.[70]

Emperor of Mexico

[edit]Background to Accession

[edit]

After gaining independence in 1821 Mexico had soon divided itself into liberal and conservative parties, the latter of which had a monarchist faction. The failed monarchy of Agustín I that saw him forced to abdicate, swearing to remain in exile, met its final demise when he returned to Mexico and was shot in 1824. Nonetheless, Conservatives continued to see monarchy as a viable option. Monarchist plans had most clearly been laid out in an 1840 essay by the statesman José María Gutiérrez de Estrada, which argued that after two decades of chaos, the republic had failed, and that a European prince ought to be invited to establish a Mexican throne. Such ideas received official interest during the presidency of Mariano Paredes and during the last presidency of Santa Anna, but by the late 1850s the liberals had appeared to have achieved a decisive victory through the promulgation of the Constitution of 1857, which constrained the powers of the Mexican Catholic Church and the Mexican Army, two traditional bastions of conservativism. Conservatives declared the Constitution null and void and formed a rival conservative government. The three-year civil war (1858–61) between liberals and conservatives was won by liberals on the battlefield. Conservatives regrouped after the defeat and sought external allies for their monarchist cause.

Mexican diplomat José Hidalgo had been officially tasked by the Santa Anna administration to sound European courts for interest in establishing a Mexican monarchy, but after the fall of Santa Anna in 1853 with the successful liberal Revolution of Ayutla, Hidalgo had lost his official accreditation and continued his efforts independently. Hidalgo's childhood friend, the Spanish noblewoman Eugénie de Montijo was now wife of Napoleon III, Emperor of France, and it was through her that Hidalgo managed to gain the attention of the French ruler.

The name of Maximilian came up swiftly in discussions among the Mexican monarchists on potential candidates for a Mexican throne. It was perceived as impolitic to propose a noble from one of the nations involved in the expedition and Maximilian already had a reputation as a capable administrator from his time spent as viceroy of Lombardy-Venetia. In 1859, Maximilian was first approached by Mexican monarchists—members of the Mexican nobility, led by José Pablo Martínez del Río—with a proposal to make him the emperor of Mexico.[71] The Habsburg family had ruled the Viceroyalty of New Spain from its establishment until the Spanish throne was inherited by the Bourbons. As a member of the House of Habsburg, Maximilian was considered to have more potential legitimacy than other royal figures. He was unlikely to ever rule in Europe because of his elder brother's position as emperor and disapproval of his younger brother's liberalism.[72] In that year, Maximilian declined the offer, but several attempts were made by the Mexican royalists. Later it was decided to again to make the offer to Maximilian, and that José María Gutiérrez de Estrada, because of his pivotal role in the history of Mexican monarchism, was to be given the role of again inviting Maximilian to assume a Mexican throne.[73]

In early 1861, the United States was embroiled in its Civil War between the southern states that had seceded and formed the Confederate States of America and the northern states that fought their efforts to secede. In these circumstances, the U.S. government could not enforce the Monroe Doctrine, which asserted U.S. pre-eminence in the hemisphere and excluded foreign intervention. In July 1861, Mexican President Benito Juárez had suspended the payment of foreign debts that had been incurred by the defeated conservative government, providing a pretext for foreign intervention. Juárez's government could ill-afford and had no desire to pay off the debts contracted by those that had challenged its legitimacy to rule. The suspension gave Napoleon III an opportunity to establish a French client state which could also serve as a buffer to the expansion of the United States. France gained the aid of Britain and Spain, which also had loaned money to the defeated conservatives, under the pretext of arranging an expedition simply to renegotiate Mexico's debt agreements. Plans for such an expedition were formalized at the Convention of London on 31 October 1861.[74]

Gutiérrez de Estrada received Maximilian's answer at the beginning of October. The Archduke would accept the throne on two conditions: first, the Mexican people themselves should spontaneously ask for him; and second, that he should also be assured of the support of France and Great Britain.[75] Maximilian's older brother, Franz Joseph Emperor of Austria, now sent Count von Rechberg, the Austrian minister of foreign affairs to brief Maximilian on what lay in store in the event that France did militarily intervene in Mexico, and a Mexican plebiscite approved of Maximilian.[76]

French invasion, Mexican conservatives, and Maximilian's agreement

[edit]In the interim, the agreement among France, the United Kingdom, and Spain broke down as it became increasingly clear that France intended to overthrow Juárez's liberal government of Mexico. France began military operations in April 1862. They were eventually joined by conservative Mexican generals who were not reconciled to their loss to the liberals in the War of Reform.[77]

After Charles de Lorencez's expeditionary force was repulsed at the Battle of Puebla on 5 May 1862, Napoleon III sent reinforcements, ultimately numbering about 38,900, and placed them under the command of General Élie Forey. Even so, it took the French a year to take Puebla, and then the capital in June 1863. The French now sought to establish a friendly Mexican provisional government. Forey appointed a committee of thirty-five Mexicans, the Junta Superior who then elected three Mexican citizens to serve as the government's executive. In turn this triumvirate then selected 215 Mexicans to form together with the Junta Superior, an Assembly of Notables.[78]

The Assembly met in July 1863 and resolved to invite Maximilian to be Emperor of Mexico. The executive triumvirate was formally changed into the Regency of the Mexican Empire. An official delegation left Mexico, arriving in Europe in October. Upon meeting the delegation, Maximilian set forth the condition that he would only accept the throne if a national plebiscite approved of it.[79] By February 1864 French forces controlled territory comprising the majority of Mexico's population. The Mexican plebiscite duly held in occupied territory "was a farce", but Maximilian accepted the proclamation that a majority of Mexicans voted in favor of him as emperor.[80]

The crown of Mexico came at a high cost to Maximilian. Although he had extracted promises from Napoleon III to militarily support the regime, he was to be entirely dependent on him. Emperor Franz Joseph isolated his younger brother Maximilian by forcing him to renounce any rights to the Austrian throne or as an archduke of Austria. On 9 April 1864 Maximilian reluctantly agreed to the "Family Pact".[81] Maximilian formally accepted the crown of Mexico at Miramar on 10 April 1864.

Arrival in Mexico

[edit]

In April 1864, Maximilian stepped down from his duties as Chief of Naval Section of the Austrian Navy. He traveled from Trieste aboard SMS Novara, escorted by the frigates SMS Bellona (Austrian) and Thémis (French), and the Imperial yacht Fantasie led the warship procession from his Miramare Castle out to sea.[82] They received a blessing from Pope Pius IX, and Queen Victoria ordered the Gibraltar garrison to fire a salute for Maximilian's passing ship.[83]

The widespread doubts amongst informed persons concerning the wisdom of Maximilian's venture were reflected by the French colonel François Claude du Barail, who while returning from arduous service in Mexico sighted the Novara during its Atlantic crossing.[84] Wrote du Barail: "If you succeed in bringing order out of this chaos, fortune into this misery, union into these hearts you will be the greatest sovereign of modern times. Go poor fool! You may regret your beautiful castle of Miramar!"[85]

The new emperor of Mexico landed at Veracruz on 29 May 1864,[86] and received a sparse reception from the townspeople due to a yellow fever outbreak.[87] The Imperial couple's arrival at the capital was more celebrated, with fireworks and hundreds of triumphant arches.[88] Maximilian and Carlota were crowned at the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral.[89][90][91] He had the backing of Mexican conservatives, nobility, clergy, some Native American populations, and numerous European monarchs, but from the very outset he found himself involved in serious difficulties, since the Liberal forces led by President Benito Juárez refused to recognize his rule. There was continuous fighting between the French expeditionary forces (who were supplemented by Maximilian's locally recruited Imperial Mexican troops) on one side and the Mexican Republicans on the other.[92]

After a brief stay at the National Palace, the emperor and empress decided to set up their residence at Chapultepec Castle, located on the top of a hill formerly on the outskirts of Mexico City that had been a retreat of Aztec emperors and Spanish viceroys. Maximilian ordered a wide avenue cut through the city from Chapultepec to the city center and named it the Paseo de la Emperatriz, the project would survive him and the Empire and is today one of the central avenues of Mexico City, the Paseo de la Reforma.[93] Maximilian also acquired a country retreat at Cuernavaca, a villa known as the Jardín Borda.[citation needed]

Rule

[edit]Although Maximilian had been brought to power with the support of Mexican conservatives expecting he would reverse the reforms of Mexican liberals, codified in the Constitution of 1857, Maximilian and Napoleon III did not want hardline Mexicans to control the regime. Napoleon III had a confidential policy known to his military commander François Achille Bazaine to marginalize the conservatives and create a moderate monarchy with wide support.[94] Maximilian was in agreement and sought to establish a regime that included liberals. In the summer of 1864 Maximilian declared a political amnesty for all liberals wishing to join the Empire. His conciliatory efforts eventually won over some moderate liberals such as José Fernando Ramírez, José María Lacunza, Manuel Orozco y Berra, and northern strongman Santiago Vidaurri, a former ally of Juárez.[95]

Maximilian's lack of understanding of the political situation on the ground in Mexico is seen in his offer to Juárez of amnesty and the post of prime minister.[96] Juárez refused and continued to assert his role as the legitimate head of the Mexican state, despite being forced to decamp from the capital to Mexico's north. He never left Mexico's national territory, continuing to be recognized by the U.S. government. Juárez had appointed Matías Romero as minister plenipotentiary to the U.S. government, an effective advocate for the Mexican republic even as the U.S. was embroiled in its civil war.[97] Juárez's continued presence in Mexico denied Maximilian assertion of legitimacy as ruler.[citation needed]

A major aspect of liberalism in Mexico was the curtailment of the power and privileges of the ideologically conservative Catholic Church, including the forced sale of Church-owned property and freedom of religion, removing Catholicism as the sole religion of the nation. The papal nuncio, Pier Francesco Meglia, arrived in Mexico in December 1864, and informed Maximilian that the liberal laws were to be reversed, Church property was to be returned and religious toleration rescinded and Catholicism as the sole religion reinstated. Maximilian refused, decreeing freedom of worship and confirmed the sale of Church property, as well as other liberal reforms. The pope's representative wrote to Maximilian, saying that the Church had supported the establishment of the empire, but now threatened that it would no longer do so if the regime were "ungodly."[98] Maximilian's alienation of the high clergy was in line with his liberal views, but it removed a major pillar of conservative support for the empire.[citation needed]

Maximilian had other priorities as well, including reorganizing his ministries and reforming the Imperial Mexican Army. Having the Imperial Mexican Army under his control would have given him as monarch an armed force and draw on its traditional base of support, but Bazaine impeded that in order to consolidate French control.[99]

During his short reign, Maximilian issued eight volumes of laws covering all aspects of government, including forest management, railroads, roads, canals, postal services, telegraphs, mining, and immigration, most of which were never implemented.[100][101] The emperor issued laws guaranteeing Mexicans' equality before the law and freedom of speech, and laws meant to defend the rights of laborers, especially that of the Natives. Maximilian attempted to implement a law guaranteeing the natives a living wage and outlawing corporal punishment for them, along with limiting their inheritance of debts. The measures faced backlash from the cabinet, but were ultimately issued during one of Carlota's regencies.[102] Labor laws in Yucatán actually became harsher on workers after the fall of the Empire.[103] A national system of free schools was also planned based on the German gymnasia, and the emperor founded an academy of sciences and literature.[104][105] Laws were published in Spanish and in Nahuatl, the Aztec language, which had the largest number of indigenous speakers. Maximilian appointed the Indigenous scholar Faustino Galicia as an advisor to his government.[106] Galicia would also be named president of the Council for the Protection of the Impoverished.[107]

The regime established an immigration agency to promote immigration from the United States, including former Confederates, such as those who immigrated to Brazil; as well as from Europe and Asia. Colonists were to be granted citizenship at once, and gained exemption from taxes for the first year, and an exemption from military services for five years. Two of the most prominent migrant communities built during this era were the New Virginia Colony and the "Carlota Colony."[108][109]

Many of Maximilian's reforms were simply revivals of previous Mexican legislation.[110] Franciso Arrangoiz who had been Maximilian's minister to Britain, Holland, and Belgium,[111] later accused Maximilian of passing such reforms to gain favorable public opinion in Europe, and to give the impression that he had a 'creative genius' and was 'lifting Mexico out of barbarism.'[112]

In August 1864 Maximilian took a state trip through the nation while Empress Carlota reigned as regent, going to Querétaro, Guanajuato, and Michoacan, giving public audiences and visiting officials. He celebrated Mexican independence by commemorating the Cry of Dolores, in the actual town where it took place.[113] In November, and December 1865, Carlota took a similar trip to Yucatán.[114]

Court life

[edit]

Maximilian lived for the most part at Chapultepec Castle, making occasional retreats to his villa at Cuernavaca, where he had also taken a mistress named Concepción Sedano.[49] He preferred to dress plainly and also enjoyed wearing traditional Mexican clothing.[115] He enjoyed the Mexican countryside and would often go horse-riding, walking, and swimming.[116] On Sundays at Chapultepec Palace, Maximilian and Carlota frequently held audiences with people from all social and economic segments, including Mexico's Indigenous peoples.[117] The royal couple also hosted multiple balls for Mexican high society.[118]

Deteriorating military situation

[edit]In April 1865, the American Civil War ended, and while the American government was reluctant to enter upon a conflict with France to enforce the Monroe Doctrine, official American sympathy remained with president Benito Juárez. The U.S. government refused to recognize the Empire and also ignored Maximilian's correspondence.[119] In December, a private American loan worth $30 million was approved for Juárez, and American volunteers kept joining the Mexican republican troops.[120] An unofficial American raid occurred near Brownsville, and Juárez's minister to the United States, Matías Romero, proposed that General Ulysses S. Grant or General William Tecumseh Sherman intervene in Mexico to help the liberals.[121] The prospect of an American invasion to reinstate Juárez caused a number of Maximilian's loyal adherents to abandon his cause and leave the capital.[122] The United States refrained from direct military intervention, but continued to put diplomatic pressure on France to leave Mexico.[123]

A concentration of French troops in the northern republican strongholds of Mexico only led to a surge of republican guerrilla activity in the south. While French troops controlled major cities, guerrillas continued to be a major military threat in the countryside. In an effort to combat the increasing violence and in a belief that Juárez had left Mexico, Maximilian in October signed a decree authorizing the court martial and execution of anyone found either aiding or participating with the guerrillas. The harsh measure resembled the 1862 measure by Juárez,[124] but it proved to be widely reviled, being branded the Black Decree. It contributed to the growing unpopularity of the Empire.[125] It is calculated that more than 11,000 Juárez supporters were executed as a result of the decree.[126][127][128]

In January 1866, seeing the war as unwinnable and the cost of keeping troops there a financial drain, Napoleon III declared to the French Corps législatif that he intended to withdraw the French military from Mexico. Maximilian's request for more aid or at least a delay in troop withdrawals was declined. Carlota arrived in Europe in an attempt to plead for the Empire's cause but was unable to gain more support. After the failure of her mission Carlota became increasingly mentally unstable. She spent the rest of her life in seclusion in Belgium, living until 1927.[129]

Fall of the Empire

[edit]

In October 1866 Maximilian moved his cabinet to Orizaba and was widely rumored to be leaving the nation. He contemplated abdication, and on 25 November held a council of his ministers to address the crisis faced by his government. They narrowly voted against abdication and Maximilian headed back towards the capital.[130] He intended to appeal to the nation in order to hold a national assembly which would then decide what form of government the Mexican nation was to take.[131] Such a measure would require a ceasefire from Juárez, who had no intention of conceding to someone whom he viewed as the puppet of the French invaders.

As the national assembly project fell through, Maximilian decided to focus on military operations, and in February 1867, as the last of the French troops were leaving, the Emperor headed for the city of Querétaro to join the bulk of his Mexican troops, numbering about 10,000 men. The liberal generals Mariano Escobedo and Ramón Corona converged on Querétaro, besieging it with 40,000 men, and yet the city held out. In the face of an increasing number of Republican troops, however, on 11 May, Maximilian resolved to attempt an escape through the enemy lines and make a break for the coast. This plan was sabotaged by Colonel Miguel López who had come to an agreement with Republican General Escobedo to open the gate to the Republican forces. López appears to have assumed that Maximilian would be allowed to escape.[132]

The city fell on 15 May 1867, and Maximilian was captured the next morning after a failed attempt to escape through Republican lines by a loyal hussar cavalry brigade led by Felix Salm-Salm. Maximilian was captured along with his generals Tomás Mejía Camacho and Miguel Miramón.[133]

Execution

[edit]

Maximilian's trial began on 13 June, in the Teatro Iturbide of Querétaro, and he was charged with conspiring to overthrow the Mexican government and with carrying out the Black Decree. Maximilian's lawyers, which included the conservative statesman Rafael Martínez de la Torre, attempted to defend the legitimacy of the Empire and Maximilian's benevolent rule.[134] After only one day the court returned a verdict of guilty and sentenced Maximilian to death.[135]

A number of the crowned heads of Europe and other prominent figures (including the eminent liberals Victor Hugo and Giuseppe Garibaldi) sent telegrams and letters to Mexico requesting that the Emperor's life be spared.[136]

Although he respected Maximilian on a personal level,[137] Juárez refused to commute the sentence because he believed it was necessary to send a message that Mexico would not tolerate any more foreign invasions.[138]

Felix Salm-Salm and his wife devised a plan to allow Maximilian to escape execution by bribing his jailors. However, Maximilian would not go through with the plan unless Generals Miramón and Mejía could accompany him and because he felt that shaving his beard to avoid recognition would undermine his dignity if he were to be recaptured.[139]

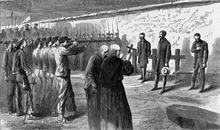

The sentence was carried out in the Cerro de las Campanas at 6:40 a.m. on the morning of 19 June 1867, when Maximilian, along with Generals Miramón and Mejía, was executed by a Republican firing squad. He spoke only in Spanish and gave each of his executioners a gold coin in traditional European aristocratic fashion. His last words were, "I forgive everyone, and I ask everyone to forgive me. May my blood which is about to be spilled end the bloodshed which has been experienced in my new motherland. Long live Mexico! Long live its independence!" A photo of Maximilian's firing squad is owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection.[140]

After Maximilian's execution, his body was embalmed and displayed in Mexico, and not repatriated to Austria until six months after his death. Photos of his corpse were taken.[140] The Austrian admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff was sent to Mexico aboard SMS Novara to take the late emperor's body back to Austria. After arriving in Trieste, the coffin was taken to Vienna and placed in the Imperial Crypt on 18 January 1868.[141]

The Emperor Maximilian Memorial Chapel was constructed on the hill where his execution took place.[142]

Cultural depictions and portrayals

[edit]

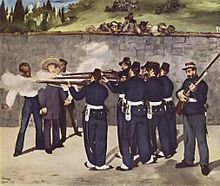

Maximilian's execution was portrayed in a series of three paintings by French painter Édouard Manet, who had Republican sympathies. His third depiction of the execution shows the Mexican soldiers wearing "uniforms almost identical to French troops, and the man preparing for the coup de grâce shares the conspicuous features of Napoleon III. The implication was clear: Napoleon III had blood on his hands. Unsurprisingly, the painting was banned from public display in Paris"[143]

In the wake of his death, carte-de-visite cards with photographs commemorating his execution circulated both among his followers and among those who wished to celebrate his death. One such card featured a photograph of the shirt he wore to his execution, riddled with bullet holes.[144]

Composer Franz Liszt included a "Marche funèbre, en mémoire de Maximilian I, empereur de Mexique" (a funeral march, in memory of Maximilian I, Emperor of Mexico) among the pieces in his famous collection of piano pieces entitled Années de pèlerinage.[145]

In Vienna, mementos of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico and of the Second Mexican Empire are on display at the Schatzkammer Museum in the Hofburg Palace,[146] at Heeresgeschichtliches Museum and at the Imperial Furniture Collection. A statue of Maximilian stands today in the 13th district of Vienna in front of the entrance to the Schönbrunn Palace Park. In Bad Ischl, the Maximilian fountain on the Traun, built in 1868, is a reminder of him.[citation needed]

In Italy, there is a statue of Maximilian in Trieste, brought back to its original place, Piazza Venezia, from the park of the Miramare Castle in 2009. Maximilian now "overlooks" part of the port of Trieste again. The Rostrata Columna, dedicated to him in 1876 in Maximilian Park in Pula, a work by Heinrich von Ferstel, was brought to Venice in 1919 as Italian spoils of war and is now, rededicated, on the edge of the Giardini della Biennale.[citation needed]

There are portrayals of Maximilian on stage, in film and television. In theater, the play by Franz Werfel Juarez and Maximilian focuses on the two historical figures; it was performed in Berlin in 1924, directed by Max Reinhardt. In cinema, the 1934 Mexican film Juárez y Maximiliano he is played by Enrique Herrera; in the 1939 American film Juarez by Brian Aherne. In the 1939 film The Mad Empress, about his wife, Maximilian was played by Conrad Nagel. Maximilian is portrayed in one scene in the 1954 American film Vera Cruz, played by George Macready. In the Mexican telenovela El Vuelo del Águila, Maximilian was portrayed by Mexican actor Mario Iván Martínez.[citation needed] The German-produced Netflix historical drama The Empress, premiering in 2022, centers on the life of Empress Elisabeth of Austria, Maximilian's sister-in-law. Maximilian, played by actor Johannes Nussbaum, is portrayed in an unfavorable light.[citation needed]

In literary fiction, Harry Turtledove's 1997 alternative history novel How Few Remain where the Confederate States of America won the American Civil War, Maximilian is still Emperor in 1881 and sells the provinces of Sonora and Chihuahua to the Confederacy for CS $3,000,000 because his country is financially strapped.[citation needed]

Conspiracy theorists writing in German allege Maximilian was not executed and that, having entered a secret agreement with Juárez, lived in exile in El Salvador as Justo Armas until 1936.[147][148][149]

Legacy

[edit]

With Maximilian's execution in 1867 by a firing squad of the restored republic, schemes and dreams of a royal head of state came to an end in Mexico. Historians are still assessing the period in Mexican history and Maximilian's role as well as that of the man he unsuccessfully aimed to depose, the liberal president of the Mexican Republic, Benito Juárez. With Maximilian's execution, the second emperor of Mexico to have met that fate following that of Agustín I of Mexico, monarchism in Mexico ceased to be a goal of Mexican conservatives.[citation needed]

Maximilian saw himself as a liberal, aligned with the ideas of Mexican liberalism, but he lacked the understanding that his position was tenuous. Liberalism implemented in Mexico by a European royal propped up by the power of Napoleon III to guarantee the repayment of a fraudulent loan was not a strong basis for enduring rule. Maximilian was initially supported by Mexican conservatives, who failed to realize Maximilian's political outlook. Far from repudiating laws of the Liberal Reform removing the privileged status of the Catholic Church in Mexico, Maximilian supported them, thereby losing support from Mexico's conservatives who had given his regime a veil of legitimacy as a Mexican project. Mexican historian Erika Pani sees Maximilian in the tradition of Mexican liberals Juárez, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, and Porfirio Díaz advocating the disentailment and nationalization of ecclesiastical properties, the dismantling of private courts for privileged corporate entities of the Catholic Church and the Mexican Army, and major infrastructure project of the building of railways in Mexico.[150] Mexican conservativism survived the execution of Maximilian, to fight the increased anticlericalism in the wake of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), but Mexican monarchism did not. Starting at the end of the twentieth century, the historiography, the writing of history, increasingly seeks not to denigrate Maximilian and the Second Mexican Empire, but to understand it.[151]

One biographer in 1971, calls Maximilian and Carlotta "tragic figures". He compares the era to that of "grand opera", with "actors on that stage [who] appear as posturing anachronisms rather than great personages ... only in terms of nineteenth-century melodrama ... does the whole affair assume the credibility of something more than a harlequinade. The blood, after all, was real. The tragedy of Maximilian and Carlotta, and that of the thousands who died or were bereft as a result of their venture in the New World, could have been the product only of a period phosphorescent with decay and delusion."[152]

Maximilian has been praised by some historians for his liberal reforms, genuine desire to help the people of Mexico, refusal to desert his loyal followers, and personal bravery during the siege of Querétaro. Other researchers consider him short-sighted in political and military affairs, and unwilling to restore republican ideals in Mexico even during the imminent collapse of the Second Mexican Empire.[citation needed]

One of the lesser-known but wide reaching influences of Maximilian's reign in Mexico involved music- Maximilian brought Central European marching bands and folk musicians with him to Mexico, and after his execution, those musicians fled to northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. There they continued playing their European-based music such as polkas and waltzes, featuring European instruments such as the accordion, but blending with local Spanish and indigenous Mexican influences. This led to the development of musical genres such as norteño and tejano, which have been and still are extremely influential in Mexican and Mexican-American music as a whole.[153][154]

In Mexico, there are no statues to Maximilian, but during the regime of Porfirio Díaz, a liberal army general who fought against the French, the Emperor Maximilian Memorial Chapel was built on the site of his and his generals' execution on the Cerro de las Campanas in Querétaro. Reportedly anti-republican and anti-liberal political groups who advocate the Second Mexican Empire, such as the far-right Nationalist Front of Mexico, founded in 2006, gather yearly in Querétaro to commemorate the deaths of Maximilian and his followers as martyrs.[155] Mexican flags and national symbols have been left at the foot of Maximilian's sarcophagus in the Imperial Crypt in Vienna. Maximilian's place in Mexican history is being reassessed by scholars seeking to understand the man and the period that brought him to his brief rule as emperor of Mexico.[citation needed]

Honours

[edit] Mexican Empire:

Mexican Empire:

Sovereign of the Imperial Order of the Mexican Eagle, 1865

Sovereign of the Imperial Order of the Mexican Eagle, 1865 Sovereign of the Imperial Order of Guadalupe

Sovereign of the Imperial Order of Guadalupe

- Foreign[156]

Austrian Empire:

Austrian Empire:

- Knight of the Golden Fleece, 1852[157]

- Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen, 1856[158]

Baden:[159]

Baden:[159]

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1856

- Grand Cross of the Zähringer Lion, 1856

Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1849[160]

Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1849[160] Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 20 May 1853[161]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 20 May 1853[161] Empire of Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross

Empire of Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross Brunswick: Grand Cross of the Order of Henry the Lion

Brunswick: Grand Cross of the Order of Henry the Lion Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 11 January 1866[162]

Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 11 January 1866[162] French Empire: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

French Empire: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Kingdom of Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer

Kingdom of Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer Kingdom of Hanover:

Kingdom of Hanover:

- Knight of St. George, 1856[163]

- Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order, 1856

Grand Duchy of Hesse:

Grand Duchy of Hesse:

- Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 11 May 1856[164]

- Grand Cross of the Merit Order of Philip the Magnanimous, 1856

Holy See:

Holy See:

- Grand Cross of the Order of Pope Pius IX

- Knight of the Collar of the Holy Sepulchre

Kingdom of Italy: Knight of the Annunciation, 29 March 1865[165]

Kingdom of Italy: Knight of the Annunciation, 29 March 1865[165] Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion

Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion, 8 June 1856

Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion, 8 June 1856 Kingdom of Portugal: Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword, 14 June 1852

Kingdom of Portugal: Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword, 14 June 1852 Kingdom of Prussia:

Kingdom of Prussia:

- Knight of the Black Eagle, 21 December 1852; with Collar, 13 January 1866

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle, 21 December 1852

Russian Empire:

Russian Empire:

Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1852[166]

Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1852[166]

Sweden-Norway: Knight of the Seraphim, with Collar, 21 April 1865[167]

Sweden-Norway: Knight of the Seraphim, with Collar, 21 April 1865[167] Grand Duchy of Tuscany: Grand Cross of St. Joseph

Grand Duchy of Tuscany: Grand Cross of St. Joseph Two Sicilies

Two Sicilies

Arms

[edit]-

Coat of arms as Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico

-

Imperial Monogram

-

Dual Cypher of Emperor Maximilian and Empress Carlota of Mexico

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Such an easy assumption of an improbable sexual relationship", said Alan Palmer, "fails to understand the nature of the attachment binding" Sophie and Reichstadt, who saw themselves as alien misfits stranded in a foreign court.[13] To Palmer, their "confidences were those of a brother and elder sister rather than of lovers".[13] "There is no documentary evidence to suggest that she and the Duke of Reichstadt were ever lovers", according to Joan Haslip.[168] "Whether the young Napoleon was actually the father of Maximilian could only be the subject of fascinating conjecture, something for courtiers and servants to gossip about on the long winter nights in the Hofburg [Palace]", said Richard O'Connor.[169] "There is not a shred of evidence to support the rumors", affirmed Jasper Ridley.[16] "It was said that Sophie confessed", continued Ridley, "in a letter to her father confessor, that Maximilian was the son of Napoleon, and that the letter was found and destroyed in 1859, but there is no reason to believe this story ... would she have had a sexual relationship with a boy whom she regarded as a child and a younger brother?"[170] The birth of two more sons after the death of Reichstadt in 1832 lessened even more the credibility of these claims.[170]

References

[edit]- ^ Maximilian I of Mexico at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (1911). "The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information".

- ^ Kemper, J. Maximilian in Mexico. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Company 1911, 17

- ^ Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, pp. 172-73

- ^ McAllen, M.M. (2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-59534-183-9.

- ^ "Emperor of Mexico executed". HISTORY. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Pani, Erika. El Segundo Imperio. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica 2004, 121-24

- ^ Haslip 1972, p. 6.

- ^ Hyde 1946, p. 4.

- ^ Haslip 1972, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Hyde 1946, p. 5.

- ^ Palmer 1994, pp. 3, 5.

- ^ a b c Palmer 1994, p. 3.

- ^ O'Connor 1971, p. 29.

- ^ Haslip 1972, p. 7.

- ^ a b Ridley 1993, p. 44.

- ^ Hyde 1946, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Hyde 1946, p. 7.

- ^ a b Haslip 1972, p. 17.

- ^ Haslip 1972, p. 11.

- ^ Haslip 1972, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Haslip 1972, p. 29.

- ^ a b Hyde 1946, p. 13.

- ^ Haslip 1972, p. 31.

- ^ Haslip 1972, p. 34.

- ^ Hyde 1946, p. 14.

- ^ Sainciuc, Lică (December 2014). Chişinăul ascuns: sau o încercare de resuscitare a memoriei unui oraş (PDF) (in Romanian). Editura Lumina. ISBN 978-9975-65-364-0. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Evocările de Miercuri: Mitul iubirii sau Îngerul cu aripi demontate". 19 February 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ https://hapes.hasdeu.md/bitstream/handle/123456789/275/P.%20510-600.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y [bare URL]

- ^ Antonio Schmidt-Brentano The Austrian admirals Volume I, 1808–1895, Library Verlag, Osnabrück 1997, pp. 93–104.

- ^ Habsburg 1868, p. 291.

- ^ Almeida 1973, p. 58.

- ^ Almeida 1973, p. 78.

- ^ Defrance 2004, p. 263.

- ^ Kramar 1999.

- ^ Duncan 2020, pp. 37–64.

- ^ Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power 172.

- ^ quoted in Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 173, and fn. 56

- ^ Rottauscher, Maximilian. With Tegetthoff at Lissa. The Memoirs of an Austrian Naval Officer 1861-66. p. Footnote 7. ISBN 978-1-908916-36-5.

- ^ Castelot 2002, pp. 53–57.

- ^ Kerckvoorde 1981, p. 35.

- ^ a b Kerckvoorde 1981, p. 36.

- ^ Bilteryst 2014, p. 70.

- ^ Kerckvoorde 1981, p. 40.

- ^ Bilteryst 2014, p. 71.

- ^ Shawcross, Edward, The Last Emperor of Mexico, pp. 164–165.

- ^ (in Spanish) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Shawcross, Edward, The Last Emperor of Mexico, p. 216.

- ^ a b McAllen, M.M (8 January 2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 222. ISBN 9781595341853.

- ^ Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997, 173

- ^ O'Connor, The Cactus Throne, 261, 338-39

- ^ "Otto's path from 'last crown prince' to European politician". Die Welt der Habsburger. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ "UPAEP | Global Innovation".

- ^ "IFG Afternoon Presentation (6/12/19)". IFG Annual Conference. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "Museo Nacional de Arte". munal.mx. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b c Defrance 2004, p. 267.

- ^ Defrance 2004, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Kerckvoorde 1981, p. 62.

- ^ Capron 1986.

- ^ Günter 1973, p. 224.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Castelot 2002, p. 84.

- ^ Castelot 2002, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Castelot 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Castelot 2002, p. 89.

- ^ Castelot 2002, p. 96.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Kerckvoorde 1981, p. 64.

- ^ Defrance 2004, p. 6.

- ^ Castelot 2002, p. 99.

- ^ "Emperador Maximiliano – A Habsburg on the Mexican Throne".

- ^ Leigh, Phil (4 October 2013). "Maximilian in Mexico".

- ^ Hidalgo, Jose Maria (1904). Proyectos de Monarquia en Mexico. F. Vazquez. p. 88.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Hidalgo, Jose Maria (1904). Proyectos de Monarquia en Mexico. F. Vázquez. p. 101.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Mexico VI:1861–1887. New York: The Bancroft Company. p. 98.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 51.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Mexico VI:1861–1887. New York: The Bancroft Company. p. 104.

- ^ Meyer, Michael C., et al. The Course of Mexican History. Tenth Edition. New York: Oxford University Press 2014, 293

- ^ Smith, Gene (1973). Maximilian and Carlotta. Morrow. pp. 147–151. ISBN 0-688-00173-4.

- ^ Haslip, Joan, Imperial Adventurer: Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, London, 1971, ISBN 0-297-00363-1

- ^ McAllen, M.M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ McAllen, M.M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Smith, Gene (1973). Maximilian and Carlota: A Tale of Romance and Tragedy. Morrow. p. 157. ISBN 0-688-00173-4.

- ^ Smith, Gene (1973). Maximilian and Carlotta. Morrow. p. 159. ISBN 0-688-00173-4.

- ^ El tifo, la fiebre amarilla y la medicina en México durante la intervención francesa

- ^ Harris Chynoweth, W. (1872). "The Fall of Maximilian, Late Emperor of Mexico: With an Historical Introduction, the Events Immediately Preceding His Acceptance of the Crown".

- ^ Butler, John Wesley (1918). History of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Mexico. University of Texas.

- ^ Campbell, Reau (1907). Campbell's New Revised Complete Guide and Descriptive Book of Mexico. Rogers & Smith Company. Pg.38 .

- ^ Putman, William Lowell (2001) Arctic Superstars. Light Technology Publishing, LLC. Pg.XVII.

- ^ Chartrand, Rene (28 July 1994). The Mexican Adventure 1861–67. Bloomsbury USA. pp. 18–23. ISBN 1-85532-430-X.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Hamnett, A Concise History of Mexico, 221

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 150.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ O'Connor, Cactus Throne 187

- ^ Shawcross, The Last Emperor, 141-44

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 152.

- ^ La legislación del Segundo Imperio (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 9.

- ^ McAllen, M.M (8 January 2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9781595341853.

- ^ McAllen, M.M (8 January 2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 182. ISBN 9781595341853.

- ^ Richmond, Douglas W. (15 April 2015). Conflict and Carnage in Yucatán: Liberals, the Second Empire, and Maya Revolutionaries, 1855–1876. University of Alabama Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780817318703.

- ^ Zamacois, Niceto (1882). Historia de Mexico: Tomo XVIII (in Spanish). J.F. Parres. p. 6.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 173.

- ^ McAllen, M.M. (8 January 2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 142. ISBN 9781595341853.

- ^ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 97.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 174.

- ^ Rolle, Andrew F. (1992). The Lost Cause: The Confederate Exodus to Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1961-6.

- ^ Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Méjico desde 1808 hasta 1867 (in Spanish). Vol. 3. Madrid, Impr. á cargo de A. Perez Dubrull. pp. 340.

- ^ "Galeria de Secretários". Secretarios de Hacienda y Crédito Público. Gobierno de México.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 173.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. pp. 154–155.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 180.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861-1887. The Bancroft Company. pp. 221–222.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 222.

- ^ McAllen, M.M (8 January 2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 169. ISBN 9781595341853.

- ^ Blasio, Jose Luis (1905). Maximiliano Intimo: El Emperador Maximiliano y su Corte. C. Bouret. p. 96.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 181.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. pp. 206–207.

- ^ Wooster, Robert (2006). "John M. Schofield and the 'Multipurpose' Army". American Nineteenth Century History. 7 (2): 173–191. doi:10.1080/14664650600809305. S2CID 143091703.

- ^ Reuter, Paul H. (1965). "United States-French Relations Regarding French Intervention in Mexico: From the Tripartite Treaty to Querétaro". Southern Quarterly. 6 (4): 469–489.

- ^ Richter, William (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Bancroft Company. p. 429.

- ^ Mayer, Brantz (1906). México, Central America and West Indies. John D. Morris and Company. p. 391.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. pp. 183–184.

- ^ Donald W. Miles (2006), Cinco de Mayo: What is Everybody Celebrating? : the Story Behind Mexico's Battle of Puebla, iUniverse, p. 196, ISBN 9780595392414

- ^ Ridley 1993, p. 229.

- ^ Shawcross, Edward, The Last Emperor of Mexico, p. 163.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 408. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 241.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 307. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. pp. 354–355. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 309–312.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 313–314.

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Maximilian and Carlota by Gene Smith, ISBN 0-245-52418-5, ISBN 978-0-245-52418-9

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 382. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Parkes 1960, p. 273.

- ^ a b Shawcross, The Last Emperor of Mexico, photo section

- ^ McAllen, M. M. (April 2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-1-59534-263-8.

- ^ Isaí Hidekel Tejada Vallejo (2010). "Preface: "El fusilamiento de Maximiliano de Habsburgo"". Manifiesto justificativo de los castigos nacionales en Querétaro (PDF). By Benito Juárez. Chamber of Deputies, LXI Legislature.

- ^ Shawcross, Edward, The Last Emperor of Mexico, New York: Basic Books, 2021, p. 282.

- ^ Floyd, Emily (25 December 2015). "Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg's Execution Shirt". mavcor.yale.edu.

- ^ "En mémoire de Maximilien I – Marche funèbre, S162d (Liszt) – from CDA67414/7 – Hyperion Records – MP3 and Lossless downloads". www.hyperion-records.co.uk.

- ^ "Szepter; Erinnerungsstück an Kaiser Maximilian I. von Mexiko". www.khm.at.

- ^ Sandra Weiss: Zweifel an Erschießung des Kaisers von Mexiko. In: Der Standard vom 24. March 2001.

- ^ Johann Lughofer: Des Kaisers neues Leben. Der Fall Maximilian von Mexiko. Vienna 2002.

- ^ Stefan Müller "Die Akte Maximilian" In. Die Zeit, 2 January 2014.

- ^ Pani, Erika. El Segundo Imperio. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica 2004, 121-22

- ^ Pani, El Segundo Imperio, 124

- ^ O'Connor, The Cactus Throne, 7-8

- ^ "Polka Influence on Mexican Music". www.expatinsurance.com. 30 March 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "How Mexico Learned To Polka". National Public Radio. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "Homage to the Martyrs of the Second Mexican Empire". Archived from the original on 3 May 2014.

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie (1866), Genealogy p. 2

- ^ Boettger, T. F. "Chevaliers de la Toisón d'Or – Knights of the Golden Fleece". La Confrérie Amicale. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ ""A Szent István Rend tagjai"". Archived from the original on 22 December 2010.

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1858), "Großherzogliche Orden" pp. 34, 48

- ^ Bayern (1858). Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Königreichs Bayern: 1858. Landesamt. p. 9.

- ^ H. Tarlier (1854). Almanach royal officiel, publié, exécution d'un arrête du roi (in French). Vol. 1. p. 37.

- ^ Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 273. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Hannover (1865), "Königliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen" p. 38

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Hessen (1865), "Großherzogliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen" p. 10

- ^ Cibrario, Luigi (1869). Notizia storica del nobilissimo ordine supremo della santissima Annunziata. Sunto degli statuti, catalogo dei cavalieri (in Italian). Eredi Botta. p. 120. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Staatshandbuch für den Freistaat Sachsen (1867) (in German), "Königliche Ritter-Orden", p. 4

- ^ Sveriges och Norges statskalender (in Swedish), 1866, p. 435, retrieved 4 April 2021 – via runeberg.org

- ^ Haslip 1972, p. 4.

- ^ O'Connor 1971, p. 31.

- ^ a b Ridley 1993, p. 45.

Further reading

[edit]In English

[edit]- Corti, Egon. Maximilian and Charlotte of Mexico. 2 vols. New York: Knopf 1928.

- Cunningham, Michele. Mexico and the Foreign Policy of Napoleon III (2001) 251 pp. online PhD version

- Duncan, Robert H. "Political Legitimization and Maximilian's Second Empire in Mexico, 1864–1867." Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 12 (1996) 273–300.

- Duncan, Robert H. "Embracing a Suitable Past: Independence Celebrations under Mexico's Second Empire, 1864–6." Journal of Latin American Studies 30.2 (1998): 249–277.

- Duncan, Robert H. (2020). ""Beneath a Rich Blaze of Golden Sunlight": The Travels of Archduke Maximilian through Brazil, 1860". Terrae Incognitae. 52 (1): 37–64. doi:10.1080/00822884.2020.1726025. ISSN 0082-2884. S2CID 213261011.

- Hanna, Alfred Jackson and Kathryn Abbey Hanna. Napoleon III and Mexico: American Triumph over Monarchy (1971).

- Harding, Bertita (1934). Phantom Crown: The Story of Maximilian & Carlota of Mexico. New York: Blue Ribbon Books. ISBN 1434468925.

- Haslip, Joan (1972). The Crown of Mexico: Maximilian and His Empress Carlota. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-086572-7.

- Habsburg, Maximilian (1868). Recollections of My Life. London R. Bentley.

- Hyde, H. Montgomery (1946). Mexican Empire: The History of Maximilian and Carlota of Mexico. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Ibsen, Kristine (2010). Maximilian, Mexico, and the Invention of Empire. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-1688-6.

- Jonas, Raymond (2024). Habsburgs on the Rio Grande: The Rise and Fall of the Second Mexican Empire. Harvard University Press.

- Krauze, Enrique (1997). Mexico: Biography of Power: A History of Modern Mexico, 1810–1996. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Mayo, C. M. The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire. Cave Creek, AZ: Unbridled Books 2009.

- McAllen, M. M. (2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. San Antonio: Trinity University Press. ISBN 978-1-59534-183-9. excerpt

- O'Connor, Richard (1971). The Cactus Throne: The Tragedy of Maximilian and Carlotta. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 0-04-972005-8.

- Palmer, Alan (1994). Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-665-1.

- Parkes, Henry (1960). A History of Mexico. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 273. ISBN 0-395-08410-5.

- Ridley, Jasper Godwin (1993). Maximilian and Juárez. Constable & Robinson. ISBN 0-09-472070-3.

- Shawcross, Edward (2021). The Last Emperor of Mexico: The Dramatic Story of the Habsburg Archduke Who Created a Kingdom in the New World. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-1541-674196. Also titled The Last Emperor of Mexico: A Disaster in the New World. London: Faber & Faber, 2022.

In other languages

[edit]- Almeida, Sylvia Lacerda Martins de (1973). Uma filha de D. Pedro I: Dona Maria Amélia (in Portuguese).

- Bilteryst, Damien (2014). Philippe comte de Flandre – Frère de Léopold II (PDF) (in French). Bruxelles: Éditions Racine. ISBN 978-2-87386-894-9.

- Capron, Victor (1986). Le Mariage de Maximilien et Charlotte. Journal du duc de Brabant. 1856–1857 (in French). Brussels.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Castelot, André (2002). Maximilien et Charlotte: La tragédie de l'ambition (in French).

- Defrance, Olivier (2004). Léopold Ier et le clan Cobourg.

- Paoli, Dominique (2008). L'Impératrice Charlotte – Le soleil noir de la mélancolie (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-02131-3.

- Günter, Treffer (1973). Molden (ed.). Die Weltumsegelung der Novara, 1857–1859 (in German). Viena.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kerckvoorde, Mia (1981). Charlotte : la passion et la fatalité.

- Kramar, Konrad (1999). Die schrulligen Habsburger: Marotten und Allüren eines Kaiserhauses (in German). Ueberreuter. ISBN 3-8000-3742-4. OCLC 46473818.

- Pani, Erika. El Segundo Imperio: Pasados de usos múltiples. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica 2004. ISBN 968-16-7259-3

External links

[edit]- Recollections of my life by Maximilian I of Mexico Vol. I at archive.org

- Recollections of my life by Maximilian I of Mexico Vol. II at archive.org